Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading John M. Lee's book: Introduction to Smooth Manifolds ...

I am focused on Chapter 1: Smooth Manifolds ...

I need some help in fully understanding Example 1.3: Projective Spaces ... ...

Example 1.3 reads as follows:

My questions are as follows:Question 1In the above example, we read:

My questions are as follows:Question 1In the above example, we read:

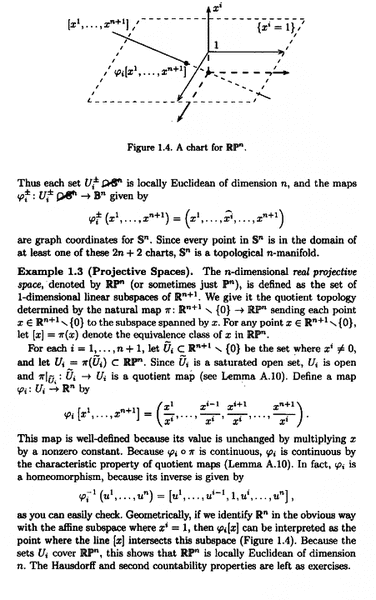

" ... ... define a map \phi_i \ : \ U_i \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^n by\phi_i [ x^1, \ ... \ ... \ , x^{n+1} ] = ( \frac{x^1}{x^i} , \ ... \ , \frac{x^{i-1}}{x^i} , \frac{x^{i+1}}{x^i}, \ ... \ , \frac{x^{n+1}}{x^i} )This map is well defined because its value is unchanged by multiplying x by a nonzero constant. ... ... "Now, in the above, the domain of \phi_i is shown as an (n+1)-dimensional point ... ... BUT ... ... \phi_i is a map with a domain consisting of lines in \mathbb{R}^{n + 1}, so shouldn't the dimension of the domain be n ... ?

Maybe we have to regard the equivalence classes of the quotient topology involved as (n+1)-dimensional points and recognise that points x = \lambda x where \lambda \in \mathbb{R} ... ... is that right?

(The statement about the map being well defined is presumably about recognising equivalence classes as on point in the projective space ... ... is that right? ... ...)

==========================================================

Question 2In the above text from Lee's book we read:

"... ... Because \phi_i \circ \pi is continuous ... ... "How do we know that \phi_i \circ \pi is continuous ... ?

============================================================

Question 3

In the above text from Lee's book we read:

"... ... In fact \phi_i is a homeomorphism, because its inverse is given by

{\phi_i}^{-1} [ u^1, \ ... \ ... \ , u^{n} ] = [ u^1, \ ... u^{i-1}, 1, u^i, \ ... \ , u^{n} ]

as you can easily check ... ... "I cannot see how Lee determined this expression to be the inverse ... why is the inverse of \phi_i of the form shown ... how do we get this expression ... and why is it continuous (as it must be since Lee declares \phi_i to be a homeomorphism ... ...

===========================================================================

Question 4

Just a general question ... in seeking a set of charts to cover \mathbb{RP}^n, why does Lee bother with the \tilde{U_i} and \pi ... why not just define the U_i as an open set of \mathbb{RP}^n and define the \phi_i ... ... ?

============================================================================Hope someone can help with the above three questions ...

Help will be appreciated ... ...

Peter

I am focused on Chapter 1: Smooth Manifolds ...

I need some help in fully understanding Example 1.3: Projective Spaces ... ...

Example 1.3 reads as follows:

" ... ... define a map \phi_i \ : \ U_i \longrightarrow \mathbb{R}^n by\phi_i [ x^1, \ ... \ ... \ , x^{n+1} ] = ( \frac{x^1}{x^i} , \ ... \ , \frac{x^{i-1}}{x^i} , \frac{x^{i+1}}{x^i}, \ ... \ , \frac{x^{n+1}}{x^i} )This map is well defined because its value is unchanged by multiplying x by a nonzero constant. ... ... "Now, in the above, the domain of \phi_i is shown as an (n+1)-dimensional point ... ... BUT ... ... \phi_i is a map with a domain consisting of lines in \mathbb{R}^{n + 1}, so shouldn't the dimension of the domain be n ... ?

Maybe we have to regard the equivalence classes of the quotient topology involved as (n+1)-dimensional points and recognise that points x = \lambda x where \lambda \in \mathbb{R} ... ... is that right?

(The statement about the map being well defined is presumably about recognising equivalence classes as on point in the projective space ... ... is that right? ... ...)

==========================================================

Question 2In the above text from Lee's book we read:

"... ... Because \phi_i \circ \pi is continuous ... ... "How do we know that \phi_i \circ \pi is continuous ... ?

============================================================

Question 3

In the above text from Lee's book we read:

"... ... In fact \phi_i is a homeomorphism, because its inverse is given by

{\phi_i}^{-1} [ u^1, \ ... \ ... \ , u^{n} ] = [ u^1, \ ... u^{i-1}, 1, u^i, \ ... \ , u^{n} ]

as you can easily check ... ... "I cannot see how Lee determined this expression to be the inverse ... why is the inverse of \phi_i of the form shown ... how do we get this expression ... and why is it continuous (as it must be since Lee declares \phi_i to be a homeomorphism ... ...

===========================================================================

Question 4

Just a general question ... in seeking a set of charts to cover \mathbb{RP}^n, why does Lee bother with the \tilde{U_i} and \pi ... why not just define the U_i as an open set of \mathbb{RP}^n and define the \phi_i ... ... ?

============================================================================Hope someone can help with the above three questions ...

Help will be appreciated ... ...

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: