A few additional comments on this interesting discussion.

1. These linear approximations are used all over the place in physics, especially introductory physics classes, to reduce difficult equations to usable ones. And they are used in many practical applications as well. Here are a few off the top of my head.

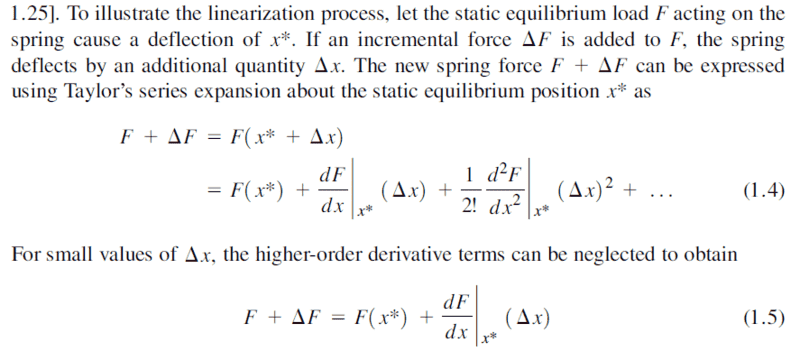

a. The potential energy of an object of mass m at height h relative to the surface of Earth is ##mgh##. No, actually it's not. The exact expression is the difference between ##GMm/R## and ##GMm/(R+h)## where R is the radius of the earth, G is the gravitational constant, and M is the mass of the earth. When ##(h/R)## is small, the linear terms of the Taylor series give you the approximation ##mgh##.

b. In a pendulum, the restoring force is proportional to the angular displacement ##\theta##, which gives you the equations for simple harmonic motion. No, actually it's not. The restoring force is proportional to ##\sin\theta##. We use the first term of the Taylor series for sine, ##\sin\theta \approx \theta##, which is pretty good for small ##\theta##.

c. The horizon when you are at height h above the surface is at ##\sqrt{2Rh}## where R is the radius of the earth. (This is one of the practical ones I mentioned, it has a lot of usage in calculations dealing with the earth. I used it many times on the job). No, actually, it's not. That's an approximation of the exact formula when ##(h/R)## is small. The exact formula, which comes from the Pythagorean Theorem, is ##\sqrt{(R+h)^2 - R^2} = \sqrt{2Rh + h^2}##.

2. When you want more accuracy, practical applications often still use series, but they keep more terms in the series. An example again from my job history is the gravitational field of the earth. For introductory physics, the Earth is a uniform sphere of mass, ##F = GMm/r^2##. For more advanced physics courses, they might introduce the variation of the density with depth and the fact that the Earth is a flattened spheroid, not a sphere. But for high-accuracy prediction of satellite motions, you need to represent the irregularities that vary over the surface. The biggest are that mountain ranges represent a high concentration of mass, and deep ocean trenches represent a lower than average concentration of mass. In those applications, the Earth is represented by a Taylor series going up to several higher powers of ##1/r##, and the coefficients of that series are derived from experimental measurements. We don't have any "original function" that the Taylor series is approximating, all we have is the series.

3. You'll also notice that the vague term "small" is used when introducing these approximations, and nobody ever defines it. How small is small enough to use the approximation? That depends on the original function, as the theory of Taylor series tells you the error after n terms depends on the n-th derivative of ##f(x)##. It also depends on how accurate an answer you need. But for many applications requiring only 2-3 significant figures, 0.1 is usually "small enough" and 0.01 is almost always "small enough".

Thanks.

Thanks.