gumby

- 3

- 0

I stumbled upon a 3-year old article from Wired that poses this question on rockets:

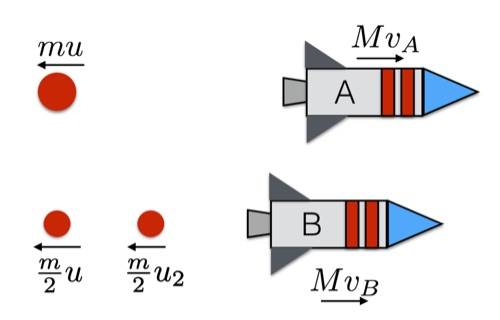

Suppose I have two rockets with a mass M and fuel mass m. Rocket A shoots all the fuel at once (again, like a nuclear propulsion engine) with a fuel speed of u and rocket B shoots two blobs of fuel—first a shot of m/2 and another one of m/2. Both start from rest. Which rocket has the higher final velocity?

Assumptions:

link to full article: https://www.wired.com/2015/10/whatd-make-better-rocket-nuclear-ion-engines/

The author claims that rocket A will have the higher velocity, but if I actually write out all the momenta, it seems to me that rocket B should be faster. I believe the author's error is that the velocity of the fuel shot from rocket A should be v_A - u not u, since u is the fuel speed relative to the rocket. Am I correct in thinking that the author is mistaken, or am I missing something?

Thanks!

Suppose I have two rockets with a mass M and fuel mass m. Rocket A shoots all the fuel at once (again, like a nuclear propulsion engine) with a fuel speed of u and rocket B shoots two blobs of fuel—first a shot of m/2 and another one of m/2. Both start from rest. Which rocket has the higher final velocity?

Assumptions:

- When fuel is expelled from a rocket, it leaves with a constant velocity that is relative to the rocket. I will call this the exhaust velocity and use the symbol u.

- Momentum is conserved when stuff is shot out the back of the rocket (I already said this).

- As fuel is consumed, the total mass of the rocket decreases. In fact, it might be easier to separate the mass into two parts: the mass of the fuel (mf) and the mass of the payload (M). Here, “payload” mass includes everything that is not fuel (rocket parts, humans, robots, computers, iPhones).

link to full article: https://www.wired.com/2015/10/whatd-make-better-rocket-nuclear-ion-engines/

The author claims that rocket A will have the higher velocity, but if I actually write out all the momenta, it seems to me that rocket B should be faster. I believe the author's error is that the velocity of the fuel shot from rocket A should be v_A - u not u, since u is the fuel speed relative to the rocket. Am I correct in thinking that the author is mistaken, or am I missing something?

Thanks!