TanWu

- 17

- 5

- Homework Statement

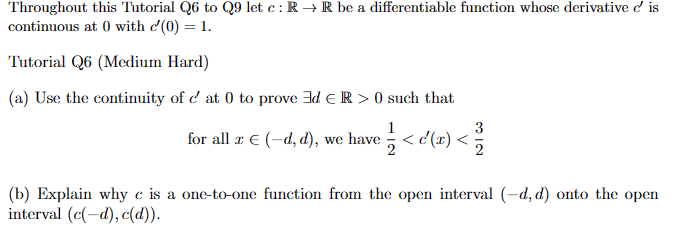

- Throughout these Tutorial Q6 to Q9 let ##c: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}## be a differentiable function whose derivative ##c^{\prime}## is continuous at 0 with ##c^{\prime}(0)=1##

- Relevant Equations

- ##c^{\prime}(0)=1##.

I am trying to solve (a) and (b) of this tutorial question.

(a) Attempt:

Since ##c'## is at ##c'(0) = 1##, then from the definition of continuity at a point:

Let ##\epsilon > 0##, then there exists ##d > 0## such that ##|x - 0| < d \implies |c'(x) - c'(0)| < \epsilon## which is equivalent to ##|x| < d \implies |c'(x) - c'(0)| < \epsilon## or ##x \in (-d, d) \implies 1 - \epsilon < c'(x) < 1 + \epsilon##

Which when comparing ##1 - \epsilon < c'(x) < 1 + \epsilon## to ##\frac{1}{2}<c^{\prime}(x)<\frac{3}{2}##, this means that ##\epsilon = \frac{1}{2}##, however, how is that possible i.e. why are we allowed to say ##\epsilon = \frac{1}{2}##? To me it seems like one is fudging the proof.

(b) Attempt:

##c## is a one-to-one function from the open interval ##(-d,d)## onto the open interval ##(-f(-d), f(d)## since it is differentiable which is equivlenet to saying that for every ##x \in dom(c)##, then there exists on and only one ##c(x) \in range(c)##

I express gratitude to those who help.

EDIT: Typos fixed.

(a) Attempt:

Since ##c'## is at ##c'(0) = 1##, then from the definition of continuity at a point:

Let ##\epsilon > 0##, then there exists ##d > 0## such that ##|x - 0| < d \implies |c'(x) - c'(0)| < \epsilon## which is equivalent to ##|x| < d \implies |c'(x) - c'(0)| < \epsilon## or ##x \in (-d, d) \implies 1 - \epsilon < c'(x) < 1 + \epsilon##

Which when comparing ##1 - \epsilon < c'(x) < 1 + \epsilon## to ##\frac{1}{2}<c^{\prime}(x)<\frac{3}{2}##, this means that ##\epsilon = \frac{1}{2}##, however, how is that possible i.e. why are we allowed to say ##\epsilon = \frac{1}{2}##? To me it seems like one is fudging the proof.

(b) Attempt:

##c## is a one-to-one function from the open interval ##(-d,d)## onto the open interval ##(-f(-d), f(d)## since it is differentiable which is equivlenet to saying that for every ##x \in dom(c)##, then there exists on and only one ##c(x) \in range(c)##

I express gratitude to those who help.

EDIT: Typos fixed.

Last edited: