- #1

hicetnunc

- 13

- 5

- Homework Statement

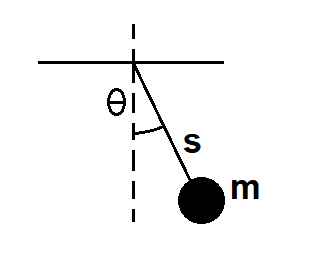

- Consider a plane pendulum of mass m and string length s. After the pendulum is set into motion, the length of the string is shortened at a constant rate. The suspension point remains fixed. Compute the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian functions. Is energy conserved?

- Relevant Equations

- Equation for the Hamiltonian

Hello!

I need some help with this problem. I've solved most of it, but I need some help with the Hamiltonian. I will run through the problem as I've solved it, but it's the Hamiltonian at the end that gives me trouble.

To find the Lagrangian, start by finding the x- and y-positions of the mass and their velocities (keeping in mind that s is not constant):

\begin{align*}

x=&s\sin(\theta)\\

y=&s\cos(\theta)\\

\\

\dot{x}=&\dot{s}\sin(\theta)+s\dot{\theta}\cos{\theta}\\

\dot{y}=&\dot{s}\cos(\theta)-s\dot{\theta}\sin{\theta}

\end{align*}

Then, the kinetic and potential energies of the system are

\begin{align*}

T=&\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{x}^2+\dot{y}^2)=\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)\\

U=&-mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

and the Lagrangian will be

\begin{align*}

L=T-U=\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)+mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

So far, so good. My solution agrees with the answer sheet I have. But, to calculate the Hamiltonian I use the equations

\begin{align*}

H=&\sum_{v}p_v\dot{q}_v-L\\

p_v=&\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_v}

\end{align*}

where the factors in the sum are the generalized momentum and generalized coordinates, respectively. From this, I get the equation

\begin{align*}

H=&\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{\theta}}\dot{\theta}+\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{s}}\dot{s}-L\\

=&\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)-mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

But this expression for the Hamiltonian is wrong! After some troubleshooting I find that if I drop the term

\begin{align*}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{s}}\dot{s}

\end{align*}

from the Hamiltonian, I get the correct answer. But why? The system needs both the coordinates theta and s to define it. Looking further at energy conservation of the system I see that in my (incorrect) solution, the Hamiltonian is expressable by T+U, and therefore energy would be conserved. But I can reason that this shouldn't be the case: Consider a small (negligible) initial angle theta and large initial string length s. Then, as time progresses, T won't change by much, but U will. Thus energy is not conserved (the answer sheet gives the reason that work is performed on the system). Why shouldn't the term above be included in the Hamiltonian?

I need some help with this problem. I've solved most of it, but I need some help with the Hamiltonian. I will run through the problem as I've solved it, but it's the Hamiltonian at the end that gives me trouble.

To find the Lagrangian, start by finding the x- and y-positions of the mass and their velocities (keeping in mind that s is not constant):

\begin{align*}

x=&s\sin(\theta)\\

y=&s\cos(\theta)\\

\\

\dot{x}=&\dot{s}\sin(\theta)+s\dot{\theta}\cos{\theta}\\

\dot{y}=&\dot{s}\cos(\theta)-s\dot{\theta}\sin{\theta}

\end{align*}

Then, the kinetic and potential energies of the system are

\begin{align*}

T=&\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{x}^2+\dot{y}^2)=\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)\\

U=&-mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

and the Lagrangian will be

\begin{align*}

L=T-U=\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)+mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

So far, so good. My solution agrees with the answer sheet I have. But, to calculate the Hamiltonian I use the equations

\begin{align*}

H=&\sum_{v}p_v\dot{q}_v-L\\

p_v=&\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{q}_v}

\end{align*}

where the factors in the sum are the generalized momentum and generalized coordinates, respectively. From this, I get the equation

\begin{align*}

H=&\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{\theta}}\dot{\theta}+\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{s}}\dot{s}-L\\

=&\frac{1}{2}m(\dot{s}^2+s^2\dot{\theta}^2)-mgs\cos{\theta}

\end{align*}

But this expression for the Hamiltonian is wrong! After some troubleshooting I find that if I drop the term

\begin{align*}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{s}}\dot{s}

\end{align*}

from the Hamiltonian, I get the correct answer. But why? The system needs both the coordinates theta and s to define it. Looking further at energy conservation of the system I see that in my (incorrect) solution, the Hamiltonian is expressable by T+U, and therefore energy would be conserved. But I can reason that this shouldn't be the case: Consider a small (negligible) initial angle theta and large initial string length s. Then, as time progresses, T won't change by much, but U will. Thus energy is not conserved (the answer sheet gives the reason that work is performed on the system). Why shouldn't the term above be included in the Hamiltonian?