DaveC426913

Gold Member

- 24,146

- 8,267

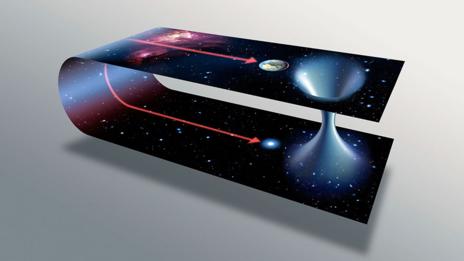

Still reading Kip Thorne's book on Interstellar. It, like so many other books that describe wormholes, shows a schematic of a wormhole like this:

It's easy to intuit that the path through the wormhole is much shorter than the path through "normal" space. But that's because they're drawn it such that normal space must curve back on itself quite dramatically.

Is this curvature of normal space a real property required for the wormhole to be a shorter distance?

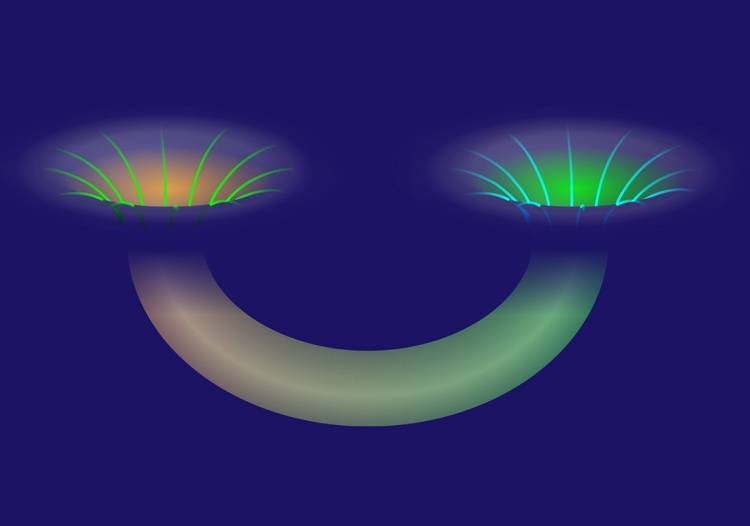

Contrast with this simple diagram:

This depicts flat space, with no huge curvature.

If one interprets it literally, the path through the wormhole is significantly longer.

So, back to the FIRST image, my question is: is the curvature depicted in the topmost diagram to be interpreted as a real curvature of space, and does it have to be in existence before the wormhole is created (i.e. independent of the WH)? This leading to the obvious question: it is likely such a curvature even exists somewhere, let alone somewhere useful to us?

Ultimately, it seems to me that, while wormholes might be hypothetically possible, we could in fact roam the universe for a cosmological age before ever finding a place with enough curvature that a wormhole could take advantage of (except perhaps within the gravity well of a black hole, where curvature is so great that we might be able to take a shortcut across an arc, from one side to another. But really, why?)

It's easy to intuit that the path through the wormhole is much shorter than the path through "normal" space. But that's because they're drawn it such that normal space must curve back on itself quite dramatically.

Is this curvature of normal space a real property required for the wormhole to be a shorter distance?

Contrast with this simple diagram:

This depicts flat space, with no huge curvature.

If one interprets it literally, the path through the wormhole is significantly longer.

So, back to the FIRST image, my question is: is the curvature depicted in the topmost diagram to be interpreted as a real curvature of space, and does it have to be in existence before the wormhole is created (i.e. independent of the WH)? This leading to the obvious question: it is likely such a curvature even exists somewhere, let alone somewhere useful to us?

Ultimately, it seems to me that, while wormholes might be hypothetically possible, we could in fact roam the universe for a cosmological age before ever finding a place with enough curvature that a wormhole could take advantage of (except perhaps within the gravity well of a black hole, where curvature is so great that we might be able to take a shortcut across an arc, from one side to another. But really, why?)

Last edited: