member 731016

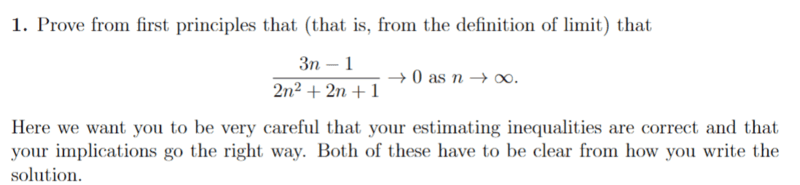

- Homework Statement

- Please see below

- Relevant Equations

- Please see below

For this problem,

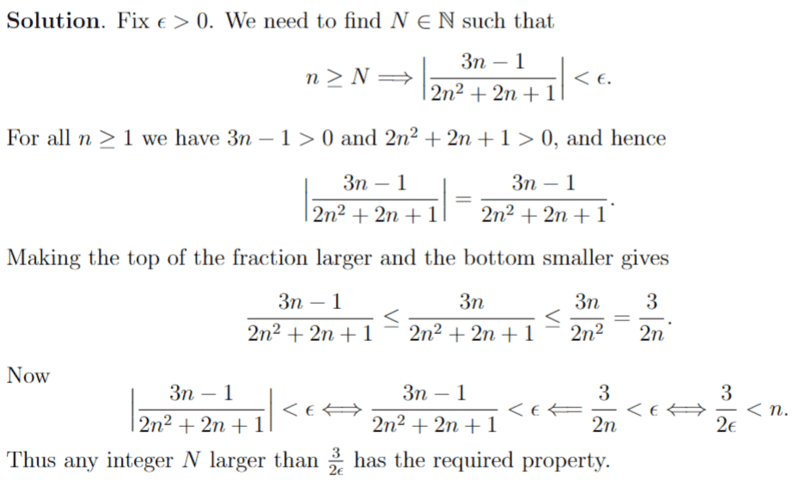

The solution is,

However, does someone please know why this did not use ##2n ≤ 2n^2 + 2n + 1## which would give

##\frac{3n - 1}{2n^2 + 2n + 1} ≤ \frac{3n}{2n} = \frac{3}{2}##?

In general, after solving many problems, it seems that when proving the convergence of a rational function from first principles, we want to find a expression for ##\epsilon## in terms of ##n## i.e ##n(\epsilon)##, which is found by making sure that there is always a ##n## in the denominator so does not cancel when finding the fraction that bounds the sequence we are trying to prove convergence from i.e something of the form ##\frac{a}{n^b}## where ##a## is a constant and ##b ≥ 1## .

However, however, is ##\frac{3}{2}## allowed for proving that this rational function converges to zero? Please correct me if I am wrong, but it means that we know for sure that the rational function in this case is bounded above by ##\frac{3}{2}## but nothing else. To me, this seems anagolus to when you don't divide out polynomial solutions, but you solve for zero. Is that the same sort of case here?

I've never seen anybody talk about not eliminating the ##n## from first principles proofs of convergence in any real analysis textbook I have read.

Thanks for any help!

The solution is,

However, does someone please know why this did not use ##2n ≤ 2n^2 + 2n + 1## which would give

##\frac{3n - 1}{2n^2 + 2n + 1} ≤ \frac{3n}{2n} = \frac{3}{2}##?

In general, after solving many problems, it seems that when proving the convergence of a rational function from first principles, we want to find a expression for ##\epsilon## in terms of ##n## i.e ##n(\epsilon)##, which is found by making sure that there is always a ##n## in the denominator so does not cancel when finding the fraction that bounds the sequence we are trying to prove convergence from i.e something of the form ##\frac{a}{n^b}## where ##a## is a constant and ##b ≥ 1## .

However, however, is ##\frac{3}{2}## allowed for proving that this rational function converges to zero? Please correct me if I am wrong, but it means that we know for sure that the rational function in this case is bounded above by ##\frac{3}{2}## but nothing else. To me, this seems anagolus to when you don't divide out polynomial solutions, but you solve for zero. Is that the same sort of case here?

I've never seen anybody talk about not eliminating the ##n## from first principles proofs of convergence in any real analysis textbook I have read.

Thanks for any help!

Last edited by a moderator: