Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

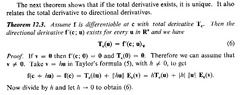

I am reading Tom M Apostol's book "Mathematical Analysis" (Second Edition) ...I am focused on Chapter 12: Multivariable Differential Calculus ... and in particular on Section 12.4: The Total Derivative ... ...I need help in order to fully understand Theorem 12.3, Section 12.4 ...Theorem 12.3 (including its proof) reads as follows:

View attachment 8505

Regarding the above Theorem, I am finding it difficult to understand how, when $$T_c(u) = f'(c;u)$$, that a function can have a finite directional derivative $$f'(c;u)$$ for every $$u$$ but may fail to be continuous at $$c$$ ... whereas! ... for a total derivative ... when a function has a total derivative it is continuous ... YET! ... $$T_c(u) = f'(c;u)$$ ...Can someone please explain what is going on ...

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

=====================================================================================

It may help MHB readers of the above post to have access to Section 12.4 on the total derivative ... so I am providing access to the same ... as follows...

View attachment 8506

View attachment 8507

It may also help MHB readers of the above post to have access to Section 12.2 on the directional derivative ... so I am providing access to the same ... as follows...

View attachment 8508

View attachment 8509

Hope that helps ...

Peter

View attachment 8505

Regarding the above Theorem, I am finding it difficult to understand how, when $$T_c(u) = f'(c;u)$$, that a function can have a finite directional derivative $$f'(c;u)$$ for every $$u$$ but may fail to be continuous at $$c$$ ... whereas! ... for a total derivative ... when a function has a total derivative it is continuous ... YET! ... $$T_c(u) = f'(c;u)$$ ...Can someone please explain what is going on ...

Help will be appreciated ...

Peter

=====================================================================================

It may help MHB readers of the above post to have access to Section 12.4 on the total derivative ... so I am providing access to the same ... as follows...

View attachment 8506

View attachment 8507

It may also help MHB readers of the above post to have access to Section 12.2 on the directional derivative ... so I am providing access to the same ... as follows...

View attachment 8508

View attachment 8509

Hope that helps ...

Peter

Attachments

-

Apostol - Theorem 12.3 .png13.5 KB · Views: 138

Apostol - Theorem 12.3 .png13.5 KB · Views: 138 -

Apostol - 1 - Section 12.4 ... PART 1 .png32.7 KB · Views: 155

Apostol - 1 - Section 12.4 ... PART 1 .png32.7 KB · Views: 155 -

Apostol - 2 - Section 12.4 ... PART 2 ... .png41.1 KB · Views: 158

Apostol - 2 - Section 12.4 ... PART 2 ... .png41.1 KB · Views: 158 -

Apostol - 1 - Section 12.2 ... PART 1 ... .png22.5 KB · Views: 136

Apostol - 1 - Section 12.2 ... PART 1 ... .png22.5 KB · Views: 136 -

Apostol - 2 - Section 12.2 ... PART 2 .png19.5 KB · Views: 133

Apostol - 2 - Section 12.2 ... PART 2 .png19.5 KB · Views: 133