Amaterasu21

- 64

- 17

Hi all,

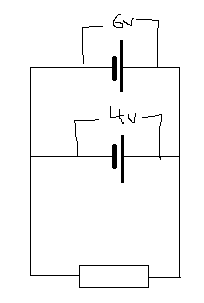

I've been thinking about a hypothetical circuit with (say) a 6V cell of negligible internal resistance, a 4V cell of negligible internal resistance, and a resistor in parallel with each other, and I can't figure out what the potential difference across the resistor would be. I've tried to apply Kirchoff's voltage rule about the emfs and p.d.s around a closed loop, but I can't see how to apply it without contradictory answers. Any help?

I've been thinking about a hypothetical circuit with (say) a 6V cell of negligible internal resistance, a 4V cell of negligible internal resistance, and a resistor in parallel with each other, and I can't figure out what the potential difference across the resistor would be. I've tried to apply Kirchoff's voltage rule about the emfs and p.d.s around a closed loop, but I can't see how to apply it without contradictory answers. Any help?