JaredJames

- 2,818

- 22

John37309 said:Well now Jarid

Ooh, bad choice. Exceptionally bad choice.

The discussion revolves around the representation of atomic nuclei, particularly in heavier elements, and how visual models might better reflect their properties. Participants explore the implications of the strong force, the structure of protons and neutrons, and the limitations of traditional visual representations.

Participants do not reach consensus; there are competing views on how to accurately represent atomic nuclei, with significant disagreement regarding the implications of the strong force and the validity of proposed visual models.

Limitations in the discussion include the reliance on visual models that may oversimplify complex interactions, as well as the challenge of accurately depicting nuclear structure based on experimental evidence.

John37309 said:Well now Jarid

John37309 said:Well now Jarid, i had no idea this forum was such a serious place. Thats really good to know!

John.

John37309 said:No, don't get me wrong. I think the standard model is great. I'm just suggesting that the visual representation of heavy nucleus's could be drawn in a way to better represent the properties we observe in experiments.

Critically, in heavy elements, using Iron as an example, we don't observe anything to suggests that Iron-52, with 26 protons and 26 neutrons, has 52 little individual bits stuck together by the strong force. What we do observe is a heavy nucleus, that physically gets bigger roughly by the cube of its mass. And with all the various fission, fusion, isotopes, and decay modes, we observe a nucleus that displays properties much closer to two bundles stuck together by the strong force. That's a bundle of protons and a bundle of neutrons, separate, but stuck together by the strong force.

I drew this image as a better representation of the properties we observe;

That image shows a Carbon, Iron and a Uranium nucleus. Below each image is an Isotope of each element with more neutrons than protons. So i displayed the neutrons in the isotope as being just a bit larger than the proton bundle. This image is physically a better representation of the properties we observe in heavy elements than the image with the single bundle of dots suggesting Iron-52 has 52 separate little bits stuck together.

John.

Thanks, that's one of the points i was trying to make. When discussing isotopes in a visual sense, this type of image has benefits. This type of image can also be adapted to more easily explain various decay modes for the nucleus.Good: right away it represents weight vs size very visually and I think it also gives the idea of about the same number (or more) of neutrons then protons

I didn't actually spend time getting the exact scale correct. It was just a quick image to discuss the topic.Not good: for small numbers of neutrons and protons (less then 20) the size rule (relative to cube of mass) is not correct.

Yea, maybe. I would disagree with you though. That compartmentalisation is also implied from the big cluster image of the nucleus. The cluster image implies that none of the protons mix together in any way. Same with the neutrons. But in reality, there is no evidence to suggest that in a heavy nucleus, the protons stay separate from each other. Or that the neutrons stay separate from each other. There is evidence to suggest that the wave functions mix together kinda like electron orbital hybridisation.Not good: it seems to imply some sort of "compartment" for the protons and neutrons being separated that way, in fact the strong force applies to each proton and neutron individually and mixing them together (as the picture in the 1st post) more strongly suggests that in a visual way.

Now that's a really good point. Let's take the Lewis structures as an example. Lewis structures have nothing what-so-ever to do with reality. But they are a really great way to explain what's happening with molecules in chemistry. So i guess that's really the point I'm making here. My type of drawing can be good for explaining some things, but not others.Currently, the only other style that does not seem to evoke too many complaints is the Lewis style of atoms, you often see the nucleus (protons and neutrons and non-valence electrons) as one circle (53 picometers for hydrogen, larger for other atoms). The various circles are shown bound with dots representing the valence electrons.

John37309 said:Yea, maybe. I would disagree with you though. That compartmentalisation is also implied from the big cluster image of the nucleus. The cluster image implies that none of the protons mix together in any way. Same with the neutrons. But in reality, there is no evidence to suggest that in a heavy nucleus, the protons stay separate from each other. Or that the neutrons stay separate from each other. There is evidence to suggest that the wave functions mix together kinda like electron orbital hybridisation.

Now that's a really good point. Let's take the Lewis structures as an example. Lewis structures have nothing what-so-ever to do with reality. But they are a really great way to explain what's happening with molecules in chemistry. So i guess that's really the point I'm making here. My type of drawing can be good for explaining some things, but not others.

Thanks for the feedback edguy99,

John.

Bruce,BruceW said:I just made a picture to represent the Woods-Saxon potential, which gives an empirical potential describing the nucleus. The basic idea is that the deeper the potential, the more likely the nucleons are to be there. The potential is deepest in the middle of the nucleus, (where its whiter), so nucleons are more likely to be in the centre.

This is probably the most scientifically accurate picture of the nucleus I have heard of. Hopefully the picture uploads correctly.

Yep, that's very true Bruce! Its a good picture, it does explain many properties of a nucleus!BruceW said:Thanks, I guess the difficulty is that you can either describe the potential of the nucleus in general, or talk about what each particle is doing individually, but it's not easy to draw a picture which explains both of them..

John37309 said:Bruce,

It kinda looks like the way people are currently drawing the electron, kinda like a cloud, as opposed to a solid particle that is orbiting at high speed. I would give that image quite high merit. I like the line of thought that suggests atoms, electrons, and even the quarks inside them are just wavy energy clouds. I like it!

John.

John37309 said:... When discussing isotopes in a visual sense, this type of image has benefits. This type of image can also be adapted to more easily explain various decay modes for the nucleus.

John37309 said:Dan,

i do like a good scientific debate, its productive. I'm not put off at all by peoples comments. If everyone patted you on the back for great suggestions, then science would be no fun.

John.

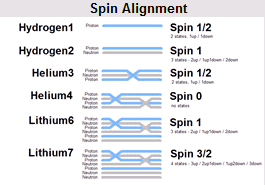

edguy99 said:I like this one, as it more properly models the binding forces and conveys the idea of coupled protons and neutrons (they don't contribute to spin). Basically these are layers of protons (blue) separated by neutron layers (grey). The only rule is you must have an insulating neutron between any two protons and the proton starts at the top (http://www.animatedphysics.com/element_spin.jpg" ).

SpectraCat said:I don't think it explains all that much ... it is just intended to help understand the microstates arising from spin coupling. For example, why aren't the spins of the lower two neutrons in lithium-7 paired? I also don't understand what you mean by "more properly models the binding forces".

edguy99 said:They don't have a proton line between them. Do you use any visual image in your mind to remember nuclear spin?

I mean by "more properly models the binding forces" that it helps you remember for instance that Helium4 is very tightly bound whereas other isotopes are less well bound - bond strength for one proton and one neutron (Hydrogen2) is about 1.1 MeV, Helium4 bond strength is almost 30 MeV (over 7 MeV per nucleon).