- 2,180

- 2,690

I have been reading Ramamurti Shankar's book "Principles of Quantum Mechanics". The author, in the first chapter, briefs out the elementary mathematics required for quantum mechanics.

Now, the author has described vector spaces, and made it very clear that only arrowed vectors that one studies in elementary physics, are not the only vectors, but matrices and functions may also be considered as vectors in a vector space consisting of such elements.

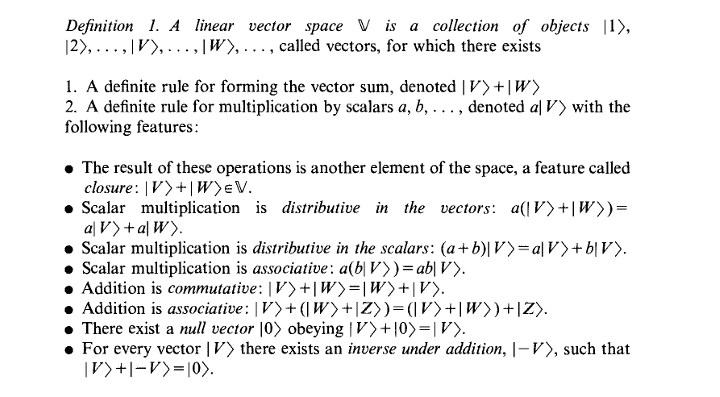

But how does something qualify as a vector? Does that quantity have to properly conform to the axioms of vectors (a picture from the book given below shows the axioms), or are there some other specific rules to which it must conform to qualify as a vector?

Now, the author has described vector spaces, and made it very clear that only arrowed vectors that one studies in elementary physics, are not the only vectors, but matrices and functions may also be considered as vectors in a vector space consisting of such elements.

But how does something qualify as a vector? Does that quantity have to properly conform to the axioms of vectors (a picture from the book given below shows the axioms), or are there some other specific rules to which it must conform to qualify as a vector?