Homework Help Overview

The discussion revolves around the concept of eigenvalues in linear algebra, specifically questioning why a scalar value, such as 1, cannot be arbitrarily defined as an eigenvalue of a given matrix. Participants are exploring the definitions and properties of eigenvalues and eigenvectors in relation to matrix operations.

Discussion Character

- Conceptual clarification, Assumption checking

Approaches and Questions Raised

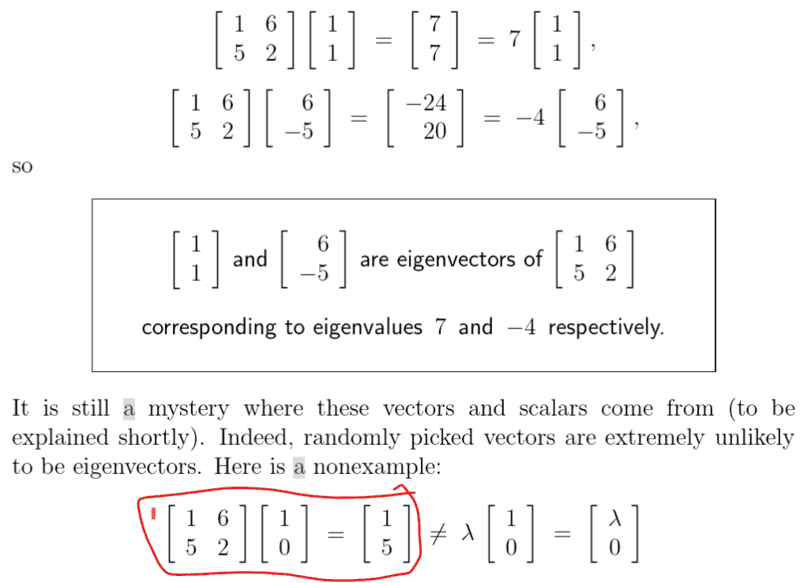

- Participants are attempting to understand the relationship between eigenvalues and eigenvectors, questioning the conditions under which a scalar can be considered an eigenvalue. There are repeated inquiries about the specific example provided and the reasoning behind the definitions.

Discussion Status

Several participants have offered clarifications regarding the definitions of eigenvalues and eigenvectors, emphasizing the requirement for the eigenvector to appear on both sides of the eigenvalue equation. Some confusion remains, but there is a productive exchange of ideas aimed at uncovering misconceptions.

Contextual Notes

There is an ongoing exploration of the definitions and properties of eigenvalues, with participants referencing a textbook that states eigenvalues can be any real number. The specific matrix and vector in question are central to the discussion, highlighting the need for clarity in the definitions being applied.