- #1

epovo

- 114

- 21

- TL;DR Summary

- The effect of a coordinate transformation on the Hamiltonian is surprising (for me!)

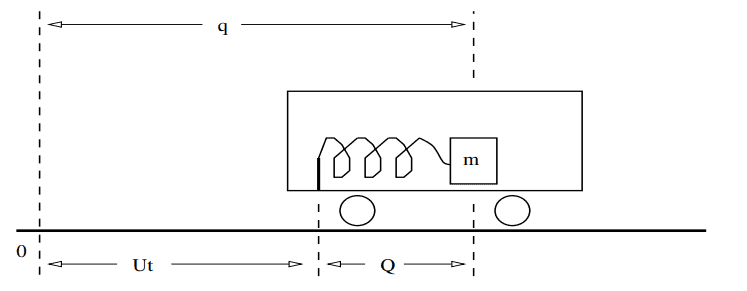

In a classical example, for a system consisting of a mass attached to a spring mounted on a massless carriage which moves with uniform velocity U, as in the image below, the Hamiltonian, using coordinate q, has two terms with U in it.

But if we use coordinate Q, ##Q=q−Ut##, which moves with the carriage, the Hamiltonian, to my surprise, still contains a term in U.

$$ H=\frac 1 2 p^2/m+Up+\frac 1 2 kQ^2 $$

By choosing coordinate Q I assumed we have moved to a static frame of reference in which U can be ignored. But that does not seem to be the case.

I could calculate the Hamiltonian as if the carriage was static, and I would of course get

$$ H=\frac 1 2 P^2/m+\frac 1 2 kQ^2 $$

I am confused.

But if we use coordinate Q, ##Q=q−Ut##, which moves with the carriage, the Hamiltonian, to my surprise, still contains a term in U.

$$ H=\frac 1 2 p^2/m+Up+\frac 1 2 kQ^2 $$

By choosing coordinate Q I assumed we have moved to a static frame of reference in which U can be ignored. But that does not seem to be the case.

I could calculate the Hamiltonian as if the carriage was static, and I would of course get

$$ H=\frac 1 2 P^2/m+\frac 1 2 kQ^2 $$

I am confused.