Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading "Abstract Algebra: Structures and Applications" by Stephen Lovett ...

I am currently focused on Chapter 7: Field Extensions ... ...

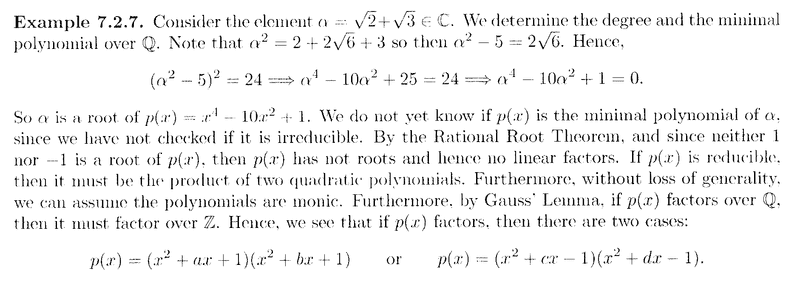

I need help with Example 7.2.7 ...Example 7.2.7 reads as follows:

In the above example from Lovett, we read the following:

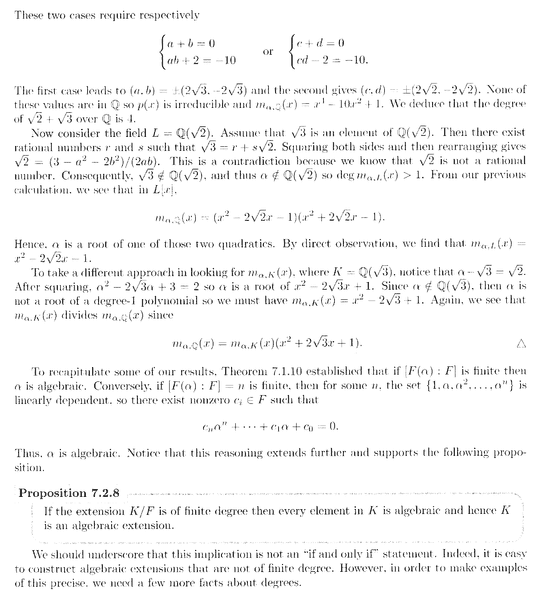

" ... ... From our previous calculation, we see that in ##L[x]##,

##m_{ \alpha , \mathbb{Q} } (x) = ( x^2 - 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1) ( x^2 + 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1)##

... ... ... "

I cannot see how this formula for the minimum polynomial in ##L[x]## is derived ...

Can someone please explain how Lovett derives the above expression for ##m_{ \alpha , \mathbb{Q} } (x) ## ... ... ?Hope someone can help ... ...

Peter

*** EDIT ***Just noted that earlier in the example we have that ##\alpha = \sqrt{2} + \sqrt{3}## is a root of

##p(x) = x^4 - 10 x^2 + 1##

which factors (in one case of two possibilities) as follows:

##p(x) = (x^2 + cx - 1) (x^2 + dx - 1)##

and this solves to ##(c,d) = \pm ( 2 \sqrt{2}, - 2 \sqrt{2} )##

... but how and why we can move from a field in which we have ##\sqrt{2}## and ##\sqrt{3}## to one in which we only have ##\sqrt{2}## ... ... I am not sure ... seems a bit slick ... ...

... indeed I certainly don't follow Lovett's next step which is to say" ... ... Hence, ##\alpha## is a root of one of those two quadratics. By direct observation, we find that

##m_{ \alpha , L } (x) = ( x^2 - 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1)## ... "Can someone please explain what is going on here ... ... in particular, why must ##\alpha## be a root of one of those two quadratics?

Peter

I am currently focused on Chapter 7: Field Extensions ... ...

I need help with Example 7.2.7 ...Example 7.2.7 reads as follows:

In the above example from Lovett, we read the following:

" ... ... From our previous calculation, we see that in ##L[x]##,

##m_{ \alpha , \mathbb{Q} } (x) = ( x^2 - 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1) ( x^2 + 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1)##

... ... ... "

I cannot see how this formula for the minimum polynomial in ##L[x]## is derived ...

Can someone please explain how Lovett derives the above expression for ##m_{ \alpha , \mathbb{Q} } (x) ## ... ... ?Hope someone can help ... ...

Peter

*** EDIT ***Just noted that earlier in the example we have that ##\alpha = \sqrt{2} + \sqrt{3}## is a root of

##p(x) = x^4 - 10 x^2 + 1##

which factors (in one case of two possibilities) as follows:

##p(x) = (x^2 + cx - 1) (x^2 + dx - 1)##

and this solves to ##(c,d) = \pm ( 2 \sqrt{2}, - 2 \sqrt{2} )##

... but how and why we can move from a field in which we have ##\sqrt{2}## and ##\sqrt{3}## to one in which we only have ##\sqrt{2}## ... ... I am not sure ... seems a bit slick ... ...

... indeed I certainly don't follow Lovett's next step which is to say" ... ... Hence, ##\alpha## is a root of one of those two quadratics. By direct observation, we find that

##m_{ \alpha , L } (x) = ( x^2 - 2 \sqrt{2} x - 1)## ... "Can someone please explain what is going on here ... ... in particular, why must ##\alpha## be a root of one of those two quadratics?

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: