archaic

- 688

- 214

- Homework Statement

- N/A

- Relevant Equations

- N/A

This is not to ask for a solution, rather I want comments on the rigor of the step. Thank you for your time!

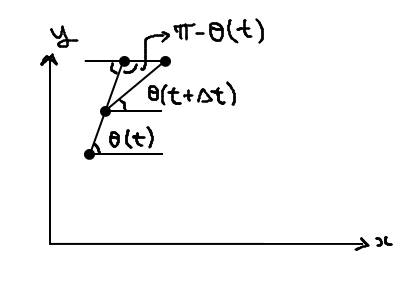

The graph shows a system of two points at ##t## and ##t+dt##, it is a bit exaggerated of course.

The upper point is moving strictly in the ##x## direction and has a constant velocity ##u##, while the lower point is always moving towards the upper point with constant velocity ##v>u##. I want to find the rate of change of the distance ##\mathcal{L}(t)## which separates them (to find the time of collision ##\tau##).

Keeping in mind that ##\cos(\pi-\theta)=-\cos(\theta)## and the cosines' law:

$$\begin{align*}

\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)&\approx(u\Delta t)^2+(\mathcal{L}(t)-v\Delta t)^2+2(u\Delta t)(\mathcal{L}(t)-v\Delta t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

&\approx(u\Delta t)^2+\mathcal{L}^2(t)-2v\mathcal{L}(t)\Delta t+(v\Delta t)^2+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t-2uv\cos(\theta(t))(\Delta t)^2

\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}

\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)-\mathcal{L}^2(t)&\approx(u\Delta t)^2-2v\mathcal{L}(t)\Delta t+(v\Delta t)^2+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t-2uv\cos(\theta(t))(\Delta t)^2\\

\frac{\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)-\mathcal{L}^2(t)}{\Delta t}&\approx u^2\Delta t-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+v^2\Delta t+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))-2uv\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t

\end{align*}$$

Now let ##\Delta t\to 0##, we have:

$$\begin{align*}

\frac{d}{dt}\mathcal{L}^2(t)&=-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

\Leftrightarrow 2\mathcal{L}(t)\mathcal{L}'(t)&=-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

\Leftrightarrow \mathcal{L}'(t)&=-v+u\cos(\theta(t))

\end{align*}$$

My problem is here, when ##t=\tau##, ##\mathcal{L}(\tau)=\mathcal{L}'(\tau)=0## and the division is then undefined. How can I go around this?

The graph shows a system of two points at ##t## and ##t+dt##, it is a bit exaggerated of course.

The upper point is moving strictly in the ##x## direction and has a constant velocity ##u##, while the lower point is always moving towards the upper point with constant velocity ##v>u##. I want to find the rate of change of the distance ##\mathcal{L}(t)## which separates them (to find the time of collision ##\tau##).

Keeping in mind that ##\cos(\pi-\theta)=-\cos(\theta)## and the cosines' law:

$$\begin{align*}

\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)&\approx(u\Delta t)^2+(\mathcal{L}(t)-v\Delta t)^2+2(u\Delta t)(\mathcal{L}(t)-v\Delta t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

&\approx(u\Delta t)^2+\mathcal{L}^2(t)-2v\mathcal{L}(t)\Delta t+(v\Delta t)^2+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t-2uv\cos(\theta(t))(\Delta t)^2

\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}

\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)-\mathcal{L}^2(t)&\approx(u\Delta t)^2-2v\mathcal{L}(t)\Delta t+(v\Delta t)^2+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t-2uv\cos(\theta(t))(\Delta t)^2\\

\frac{\mathcal{L}^2(t+\Delta t)-\mathcal{L}^2(t)}{\Delta t}&\approx u^2\Delta t-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+v^2\Delta t+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))-2uv\cos(\theta(t))\Delta t

\end{align*}$$

Now let ##\Delta t\to 0##, we have:

$$\begin{align*}

\frac{d}{dt}\mathcal{L}^2(t)&=-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

\Leftrightarrow 2\mathcal{L}(t)\mathcal{L}'(t)&=-2v\mathcal{L}(t)+2u\mathcal{L}(t)\cos(\theta(t))\\

\Leftrightarrow \mathcal{L}'(t)&=-v+u\cos(\theta(t))

\end{align*}$$

My problem is here, when ##t=\tau##, ##\mathcal{L}(\tau)=\mathcal{L}'(\tau)=0## and the division is then undefined. How can I go around this?