Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around the Euler-Lagrange equations and the conditions under which the parameter \( u \) can be considered small in the context of Taylor expansions and functional derivatives. Participants explore the implications of this assumption and its necessity for deriving the equations, as well as alternative approaches to understanding the problem.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Debate/contested

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

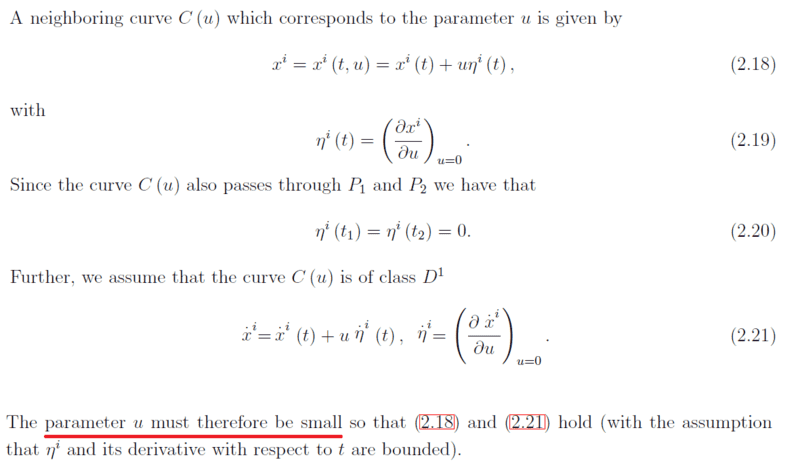

- One participant notes that the smallness of \( u \) is sometimes justified by Taylor expansion, while questioning its necessity in the context of specific equations.

- Another participant argues that neglecting higher-order terms in the Taylor series is only valid if \( u \) is small, emphasizing the need for this condition in deriving the Euler-Lagrange equations.

- A different viewpoint suggests that the equations should hold regardless of the size of \( u \), proposing that a first-order Taylor expansion is exact and can be used to prove necessary conditions without assuming \( u \) is small.

- One participant presents an alternative method for finding extrema of functions, detailing the derivation of the Euler-Lagrange equations through the evaluation of a functional derivative and integration by parts, asserting that this method is easier to understand.

- Another participant expresses confidence in understanding the alternative method but struggles with the approach presented in their study guide.

- A later reply questions the validity of a previous participant's proof, suggesting that their calculations implicitly assume the size of \( u \) and thus may not be as independent of this condition as claimed.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants exhibit disagreement regarding the necessity of \( u \) being small for the derivation of the Euler-Lagrange equations. Some argue it is essential, while others believe the equations can be derived without this assumption. The discussion remains unresolved with multiple competing views present.

Contextual Notes

Participants reference specific equations and mathematical formulations, but there are unresolved assumptions regarding the behavior of \( u \) and the implications of Taylor series truncation. The discussion also highlights varying interpretations of the derivation process and its prerequisites.

Who May Find This Useful

This discussion may be useful for students and researchers interested in variational calculus, the derivation of the Euler-Lagrange equations, and the implications of assumptions in mathematical modeling.