Discussion Overview

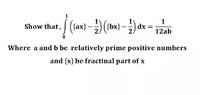

The discussion revolves around evaluating an integral involving the fractional part function, specifically in the context of two coprime integers \(a\) and \(b\). Participants explore different cases for the values of \(a\) and \(b\), and how to approach the integral through various mathematical techniques and reasoning.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Mathematical reasoning

- Debate/contested

Main Points Raised

- One participant proposes dividing the unit interval into \(ab\) subintervals and expresses the fractional parts of \(ax\) and \(bx\) in terms of \(r\) and \(t\).

- Another participant expresses confusion about the expression for the fractional part of \(ax\) and seeks clarification on the mathematical reasoning behind it.

- A participant provides a specific example with \(a=3\) and \(b=5\) to illustrate the integral calculation, showing the steps taken to derive the fractional parts.

- Some participants question whether there might be a simpler method to approach the integral, indicating uncertainty about the complexity of the current method.

- One participant discusses the implications of the coprimality of \(a\) and \(b\) on the uniqueness of the pairs \((k, l)\) derived from \(r\), suggesting that each value of \(r\) corresponds to a unique pair.

- Another participant attempts to reason why the fractional part of \(ax\) can be expressed as the sum of the fractional part of \(\frac{r}{b}\) and \(at\), while also questioning if there is a formal mathematical justification for this.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express various viewpoints on the approach to the integral, with some agreeing on the method of dividing the interval and others questioning the clarity and correctness of the expressions used. The discussion remains unresolved regarding the best approach and the understanding of the fractional part function.

Contextual Notes

Participants note that their understanding of the problem is influenced by their educational background, with some expressing that the concepts discussed are beyond their current curriculum. There is also mention of the need for a deeper understanding of number theory to fully grasp the implications of the coprimality condition.