SUMMARY

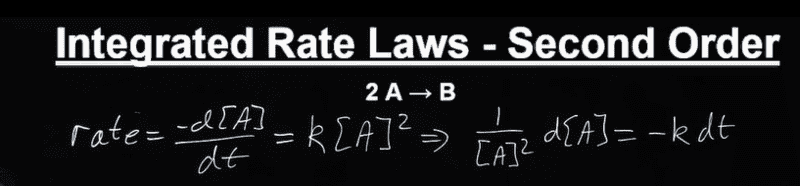

The integrated rate law for second-order reactions is defined without including stoichiometric coefficients in the rate expression. The rate of reaction is universally defined as (1/a)*d[A]/dt, where 'a' represents the stoichiometric coefficient. This approach ensures consistency across different reactants, regardless of their coefficients in the balanced equation. For example, the rate expressions differ for reactions such as A → ½B and 4A → 2B, emphasizing the importance of specifying the reagent in question.

PREREQUISITES

- Understanding of chemical kinetics

- Familiarity with stoichiometric coefficients

- Knowledge of reaction rate definitions

- Basic principles of reaction mechanisms

NEXT STEPS

- Study the derivation of integrated rate laws for second-order reactions

- Learn about the impact of stoichiometry on reaction rates

- Explore examples of second-order reactions in chemical kinetics

- Investigate the application of rate laws in real-world chemical processes

USEFUL FOR

Chemistry students, educators in chemical kinetics, and professionals involved in reaction mechanism analysis will benefit from this discussion.