Nikhil Rajagopalan said:

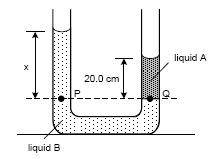

A liquid in a U-tube maintains the same level in both the arms. When another liquid which does not mix with the first one is poured in it, the air interface with either of the liquids in both the arms will be at different levels.

View attachment 216053

Considering a point at the top surface of liquid A, the pressure there should be atmospheric pressure. Another point in liquid B taken at the same level will have a pressure that amounts to atmospheric pressure plus the pressure due to the column of liquid B over it. These cannot be same. So how is the pressure at the same depth not being equal when we use that principle to solve many problems.

You have correctly reasoned that the pressures 20 cm above P and Q in the two tubes will not be the same.

Often we deal with tanks in which there is only one fluid and that fluid's density is constant. In these tanks we often take it for granted that there is a path through the fluid from any point to any other point. And finally, these situations are often static -- the fluid has been allowed to settle down into an equilibrium with no waves, no flow and no sloshing from side to side. In such circumstances, the pressure within the fluid is a simple function of depth: ##p=\rho g h## where ##\rho## is the fluid density, g is the local acceleration of gravity and h is the depth below the reference height. ["Gauge" pressure is taken to be zero at the reference height].

Clearly, in such circumstances, this means that the pressure at two points at the same depth will be identical. Break anyone of the three conditions (same fluid density, connected path, motionless fluid) and the guarantee no longer holds. [Technically, a fourth condition is also required -- gravity must be uniform across the area of interest]

But let us discard the ##p = \rho g h## and try to derive the equal pressure guarantee from first principles. Suppose that you are at point A somewhere in the fluid. The pressure there is P. Now you trace a path through the fluid to point B.

[Note that here we used the "connected" condition]

As you trace the path, every time the path goes downward by an increment of ##d h##, you will add ##\rho g\ dh## to the pressure. If this pressure increase were not present, the tiny volume of fluid at this point on the path would be subject to an unbalanced net force. It would accelerate. But we have assumed that the fluid is in equilibrium. Similarly, ever time the path goes upward by an increment of ##dh## you will subtract ##\rho g\ dh## from the pressure.

The concept of tracing the path and adding up little contributions from incremental path segments is known in vector calculus: a "path integral".

[Note that here we used the "motionless at equilibrium" condition]

If the start and end points are at the same height then when you finish tracing the path, the sum of ##d h## values must be zero. If the fluid has constant density and if gravity is constant then this means that the sum of the ##\rho g\ dh## must also be zero.

[Note that here we used the "fluid of constant density" condition]

To summarize: There are conditions that must hold before the "equal pressure at equal depths" principle can be known to be true.