Homework Help Overview

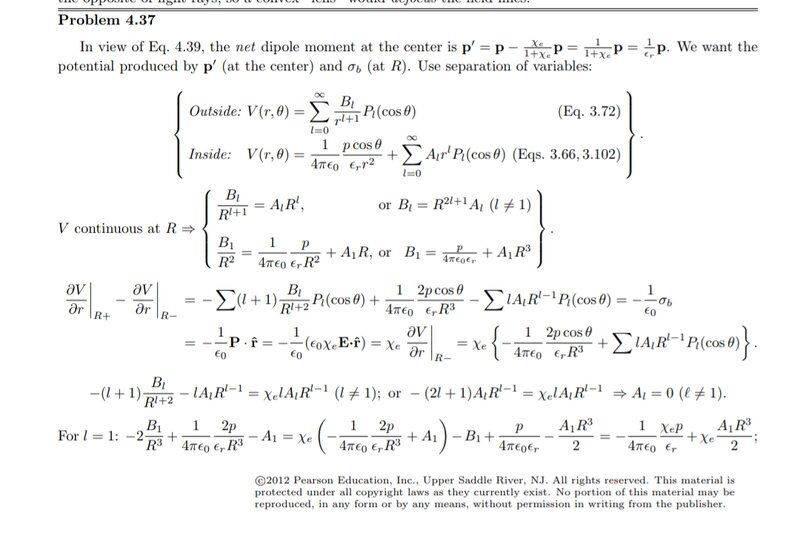

The discussion revolves around the application of Laplace's equation in the context of a point dipole, particularly addressing the confusion regarding the necessity of Poisson's equation due to the presence of a dipole moment. Participants explore the implications of charge density and potential in this scenario.

Discussion Character

- Conceptual clarification, Assumption checking

Approaches and Questions Raised

- Some participants attempt to reconcile the use of Laplace's equation despite the presence of a dipole, questioning whether the charge density being zero everywhere is valid. Others suggest that the dipole can be treated as a boundary condition for the potential that satisfies Laplace's equation outside the dipole's location.

Discussion Status

The discussion is ongoing, with participants providing insights into the nature of charge distributions and their singularities. There is a recognition of the complexities involved in treating point dipoles and the implications for the governing equations, though no consensus has been reached.

Contextual Notes

Participants note that the charge distribution is not zero everywhere, specifically highlighting the singularity at the dipole's location. The discussion also references the Dirac distribution in relation to point charges and dipoles.