Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading "Multidimensional Real Analysis I: Differentiation" by J. J. Duistermaat and J. A. C. Kolk ...

I am focused on Chapter 2: Differentiation ... ...

I need help with an aspect of the proof of Proposition 2.3.2 ... ...

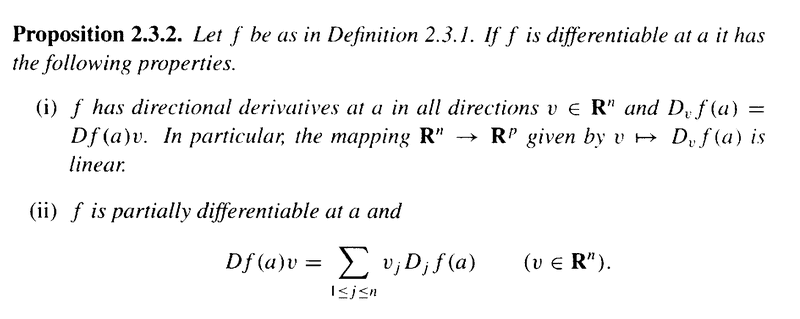

Duistermaat and Kolk's Proposition 2.3.2 and its proof read as follows:

In the above proof by D&K we read the following:

" ... ... Assertion (i) follows from Formula (2.11). ... ..."Can someone please demonstrate (formally and rigorously) that this is the case ... that is that assertion (i) follows from Formula (2.11). ... ...Help will be appreciated ...

Peter==========================================================================================***NOTE***

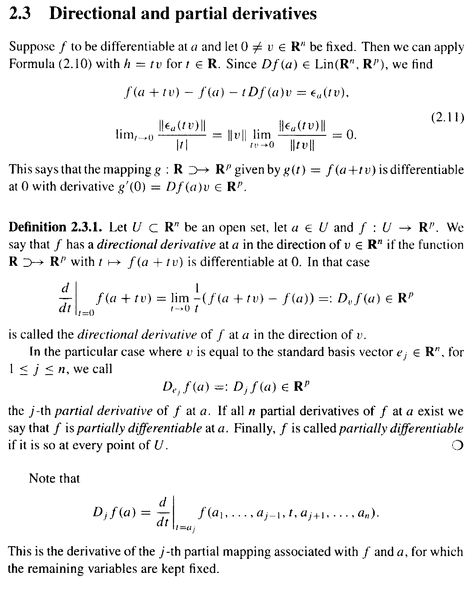

It may help readers of the above post to have access to the start of Section "2.3: Directional and Partial Derivatives" ... in order to understand the context and notation of the post ... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Hope that the above helps readers of the post understand the context and notation of the post ...

Peter

I am focused on Chapter 2: Differentiation ... ...

I need help with an aspect of the proof of Proposition 2.3.2 ... ...

Duistermaat and Kolk's Proposition 2.3.2 and its proof read as follows:

In the above proof by D&K we read the following:

" ... ... Assertion (i) follows from Formula (2.11). ... ..."Can someone please demonstrate (formally and rigorously) that this is the case ... that is that assertion (i) follows from Formula (2.11). ... ...Help will be appreciated ...

Peter==========================================================================================***NOTE***

It may help readers of the above post to have access to the start of Section "2.3: Directional and Partial Derivatives" ... in order to understand the context and notation of the post ... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Hope that the above helps readers of the post understand the context and notation of the post ...

Peter