SUMMARY

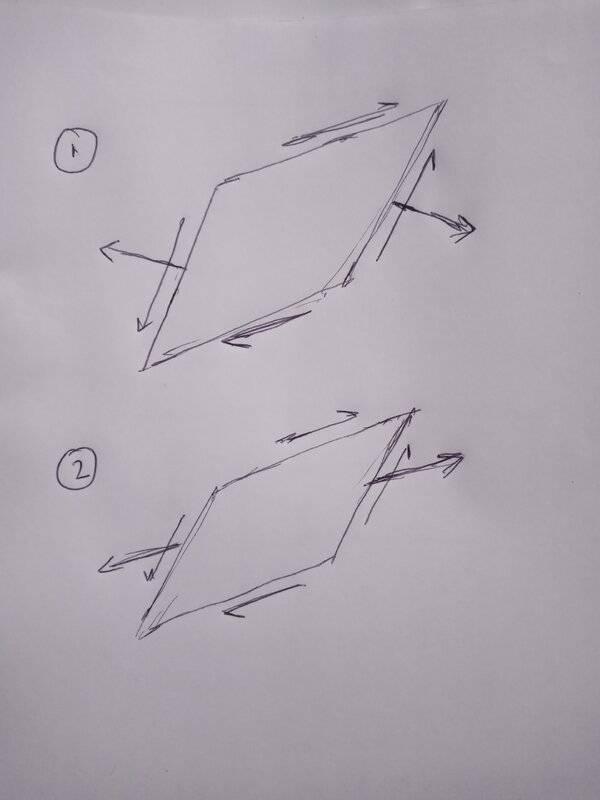

The discussion centers on the behavior of normal stress vectors in relation to material deformation, specifically addressing whether these vectors should remain normal to the surface or align parallel to another surface during deformation. Participants clarify the distinction between the second-order stress tensor and the first-order stress vector, emphasizing the importance of the Cauchy stress relationship in three-dimensional stress analysis. The conversation highlights the invariance of the stress tensor and traction vector across coordinate systems and introduces dyadic tensor notation as a valuable tool for understanding these concepts. Additionally, the implications of small versus large deformations on stress behavior are discussed, particularly in the context of linear material behavior.

PREREQUISITES

- Cauchy stress tensor

- Dyadic tensor notation

- Stress transformation techniques

- Understanding of linear and non-linear material behavior

NEXT STEPS

- Study the Cauchy-Green deformation tensor for large deformation analysis

- Explore dyadic tensor notation in detail for stress analysis

- Learn about stress transformation methods in three-dimensional contexts

- Investigate the mathematical principles of linear versus non-linear material behavior

USEFUL FOR

Mechanical engineers, materials scientists, and students studying solid mechanics or continuum mechanics who are interested in the behavior of stress vectors during material deformation.