Elwin.Martin

- 202

- 0

I've been trying to learn the basics of the Lagrangian formulation of Mechanics and I skipped over something that I'd like to ask about (I basically just took it for granted and did problems assuming it to be true).

Most of the books I've looked at introduce action as the integral of the Lagrangian for a given interval. I've read that q and \dot{q} are enough to define a system's Lagrangian. Is there a proof for the least action principle or am I just missing something really obvious?

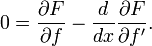

I have another question too, this one is math related though. Most of the resources I've looked at state that the condition for an extremum is that the first variation should be zero. This leads to an integral of the Lagrangian that simplifies to [see attached image] and this leads to Lagrange's equations (something along the lines of

Wiki says that the last step is a result of the "Fundamental Lemma of Calculus of Variations" but I'm just missing something that is supposed to be obvious here, again.

Thank you for your time, any and all help is greatly appreciated.

Elwin

Most of the books I've looked at introduce action as the integral of the Lagrangian for a given interval. I've read that q and \dot{q} are enough to define a system's Lagrangian. Is there a proof for the least action principle or am I just missing something really obvious?

I have another question too, this one is math related though. Most of the resources I've looked at state that the condition for an extremum is that the first variation should be zero. This leads to an integral of the Lagrangian that simplifies to [see attached image] and this leads to Lagrange's equations (something along the lines of

Wiki says that the last step is a result of the "Fundamental Lemma of Calculus of Variations" but I'm just missing something that is supposed to be obvious here, again.

Thank you for your time, any and all help is greatly appreciated.

Elwin