Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around the theoretical possibility of floating an ocean liner in a bucket of water. Participants explore concepts of buoyancy, displacement, and the conditions necessary for a vessel to float, considering various hypothetical scenarios and constraints.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Debate/contested

- Conceptual clarification

Main Points Raised

- Some participants suggest that any object with a total density less than water can float if the water is deep enough.

- Others propose that a vessel floats by displacing a mass of water equal to its own weight, emphasizing the importance of the volume of water displaced.

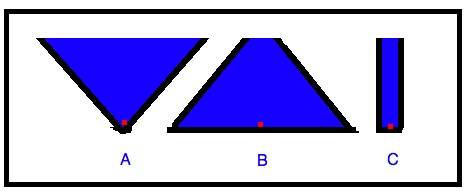

- A few participants argue that the size and shape of the bucket are critical, with one suggesting a bucket shaped like the hull of the ship could theoretically allow it to float with minimal water.

- There is a contention regarding whether a ship can float if the displaced water flows over the edge of the bucket, with some asserting that without the displaced water, the ship cannot float.

- Some participants introduce thought experiments to illustrate their points, such as comparing a boat floating in a large body of water to one in a small container.

- One participant mentions that water exerts pressure on the hull, which could theoretically allow a ship to float in a very small amount of water, although others challenge this view.

- There are claims that if the water is retained, the ship will float, while if it flows out, the ship will not be supported.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express multiple competing views on the conditions necessary for an ocean liner to float in a bucket of water. There is no consensus on whether it is feasible under the proposed scenarios, and the discussion remains unresolved.

Contextual Notes

Participants highlight limitations in their thought experiments, such as the need for sufficient water to allow for displacement and the implications of water flowing out of the bucket. The discussion also reflects varying interpretations of buoyancy principles.