TanWu

- 17

- 5

- Homework Statement

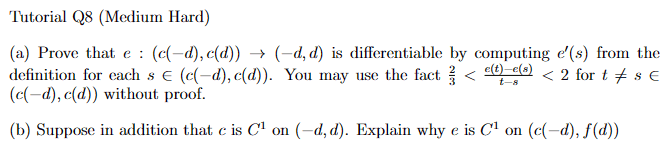

- Prove that ##e:(c(-d), c(d)) \rightarrow(-d, d)## is differentiable by computing ##e^{\prime}(s)## from the definition for each ##s \in (c(-d), c(d))##. You may use the fact ##\frac{2}{3} < \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < 2## for ##t \neq s \in (c(-d), c(d))## without proof.

- Relevant Equations

- ##\lim_{t \to s} \frac{2}{3} < \lim_{t \to s} \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < \lim_{t \to s} 2##

I am trying to solve (a) and (b) of this question.

(a) Attempt

We know that ##\frac{2}{3} < \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < 2## for ##t \neq s \in (c(-d), c(d))##

Thus, taking the limits of both sides, then

##\lim_{t \to s} \frac{2}{3} < \lim_{t \to s} \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < \lim_{t \to s} 2##

Or equivalently,

##\frac{2}{3} < \lim_{t \to s} \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < 2##

##\frac{2}{3} < e'(s) < 2##

Thus, using the squeeze principle, then ##e'(s)## is bounded between ##\frac{2}{3}## and ##2##, then the derivative exists for ##t \in (c(-d), c(d))## and thus we have proved that ##e(s)## is differentiable on the required interval. Are we allowed to do that?

(b) Attempt

Since ##c(x)## is ##C^1## on (-d, d) and as we proved in (a), then e must be ##C^1## on ##(e(-d), e(d))## as it is differentiable and thus continuous. This seems somewhat too trivial of a question to me.

I express gratitude to those who help.

(a) Attempt

We know that ##\frac{2}{3} < \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < 2## for ##t \neq s \in (c(-d), c(d))##

Thus, taking the limits of both sides, then

##\lim_{t \to s} \frac{2}{3} < \lim_{t \to s} \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < \lim_{t \to s} 2##

Or equivalently,

##\frac{2}{3} < \lim_{t \to s} \frac{e(t) - e(s)}{t - s} < 2##

##\frac{2}{3} < e'(s) < 2##

Thus, using the squeeze principle, then ##e'(s)## is bounded between ##\frac{2}{3}## and ##2##, then the derivative exists for ##t \in (c(-d), c(d))## and thus we have proved that ##e(s)## is differentiable on the required interval. Are we allowed to do that?

(b) Attempt

Since ##c(x)## is ##C^1## on (-d, d) and as we proved in (a), then e must be ##C^1## on ##(e(-d), e(d))## as it is differentiable and thus continuous. This seems somewhat too trivial of a question to me.

I express gratitude to those who help.