SUMMARY

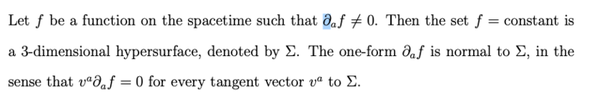

In the context of general relativity, hypersurfaces are defined by the condition that the partial derivative of a function, denoted as ##\partial_a f##, must be non-zero at the hypersurface corresponding to a constant value of the function. This is illustrated through the example of a sphere defined by the function ##f = x^2 + y^2 + z^2##, where the level surface for ##f = R^2## represents a sphere of radius ##R## in ##\mathbb R^3##. The discussion clarifies that while the gradient of a function at a contour line is perpendicular and non-zero, the strict requirement for ##\partial_a f## to be zero everywhere is not necessary for defining a hypersurface.

PREREQUISITES

- Understanding of general relativity concepts

- Familiarity with partial differential equations

- Knowledge of gradient and contour lines in multivariable calculus

- Basic understanding of manifolds and foliations

NEXT STEPS

- Study the properties of hypersurfaces in differential geometry

- Learn about the implications of gradient vectors in multivariable functions

- Explore the concept of foliations in manifold theory

- Investigate the role of level surfaces in general relativity

USEFUL FOR

Students and researchers in physics, particularly those focusing on general relativity, as well as mathematicians interested in differential geometry and manifold theory.