Happiness

- 686

- 30

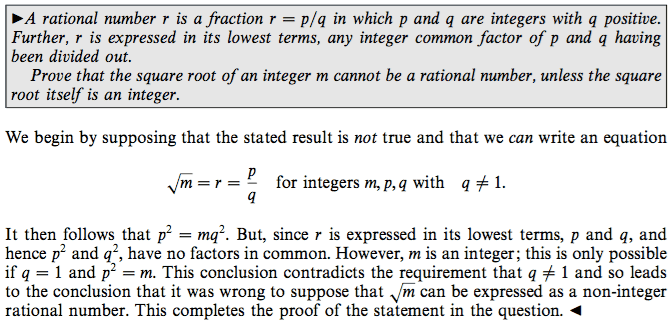

Integers ##p## and ##q## having no common factors implies ##p^2## and ##q^2## have no common factors. Could you prove this without using the fundamental theorem of arithmetic (every integer greater than 1 either is prime itself or is the product of prime numbers, and that this product is unique, up to the order of the factors)?

Note that this isn't the same as saying integers ##p## and ##q## having a common factor implies ##p^2## and ##q^2## have a common factor, which is straightforward.

The above proposition is obtained from the following proof (last paragraph, line 1). I believe the book does't use the fundamental theorem of arithmetic because if it does (implicitly require it for the above proposition) then it might as well use it right from the start for the following proof, i.e., let ##m## be a product of primes.

Note that ##p^2## has more factors than ##p##. For example, ##12## is a factor of ##p^2=36## but not of ##p=6##. That's why the proposition is not immediately obvious.

Note that this isn't the same as saying integers ##p## and ##q## having a common factor implies ##p^2## and ##q^2## have a common factor, which is straightforward.

The above proposition is obtained from the following proof (last paragraph, line 1). I believe the book does't use the fundamental theorem of arithmetic because if it does (implicitly require it for the above proposition) then it might as well use it right from the start for the following proof, i.e., let ##m## be a product of primes.

Note that ##p^2## has more factors than ##p##. For example, ##12## is a factor of ##p^2=36## but not of ##p=6##. That's why the proposition is not immediately obvious.

Last edited: