Valour549

- 57

- 4

- Homework Statement

- Please see below

- Relevant Equations

- Please see below

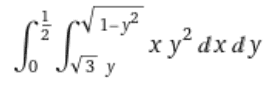

I am trying to do the double integral.

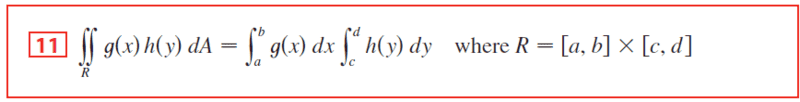

And I remembered there's this formula that says if the integrand can be split into products of F(x) and G(y) then we can do each one separately, then take the product of each result. Taken from Stewart's Calculus 9E.

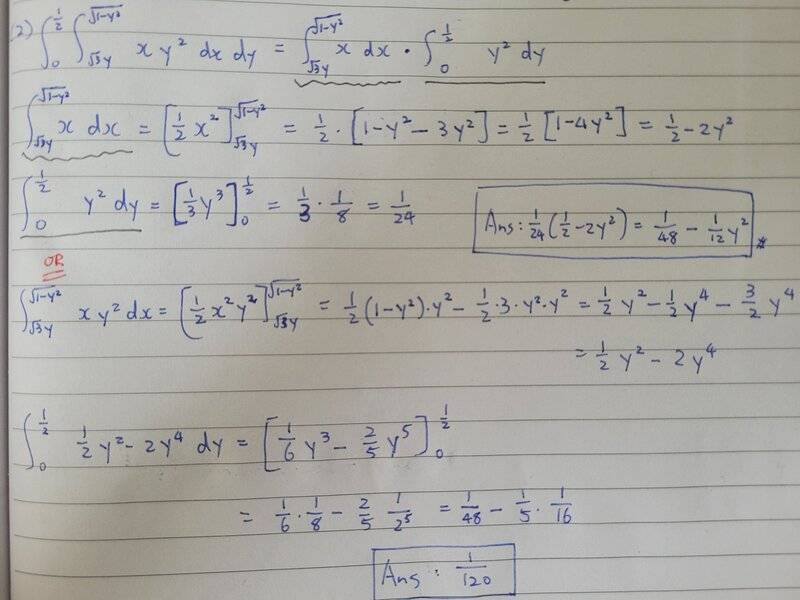

So I tried to do the integral two ways, the first is splitting them and the second not.

I'm fairly sure the correct answer is the second one. So is the right conclusion that formula above doesn't work when the limits of integration are variables, and only work when the limits of integration are pure numbers? Stewart does not caution this, and I myself cannot figure out why the formula suddenly doesn't work when the limits of integration are variables.

And I remembered there's this formula that says if the integrand can be split into products of F(x) and G(y) then we can do each one separately, then take the product of each result. Taken from Stewart's Calculus 9E.

So I tried to do the integral two ways, the first is splitting them and the second not.

I'm fairly sure the correct answer is the second one. So is the right conclusion that formula above doesn't work when the limits of integration are variables, and only work when the limits of integration are pure numbers? Stewart does not caution this, and I myself cannot figure out why the formula suddenly doesn't work when the limits of integration are variables.