Abdullah Almosalami

- 49

- 15

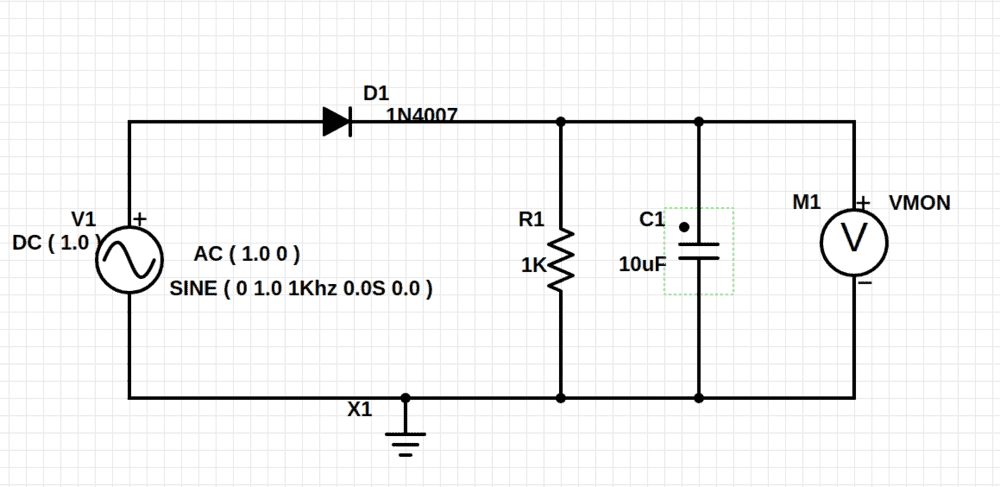

This has been frustrating me to no end, and I can't really find an answer in any textbook. So, here's my issue. A basic half-wave rectifier circuit with just a reservoir capacitor looks like this:

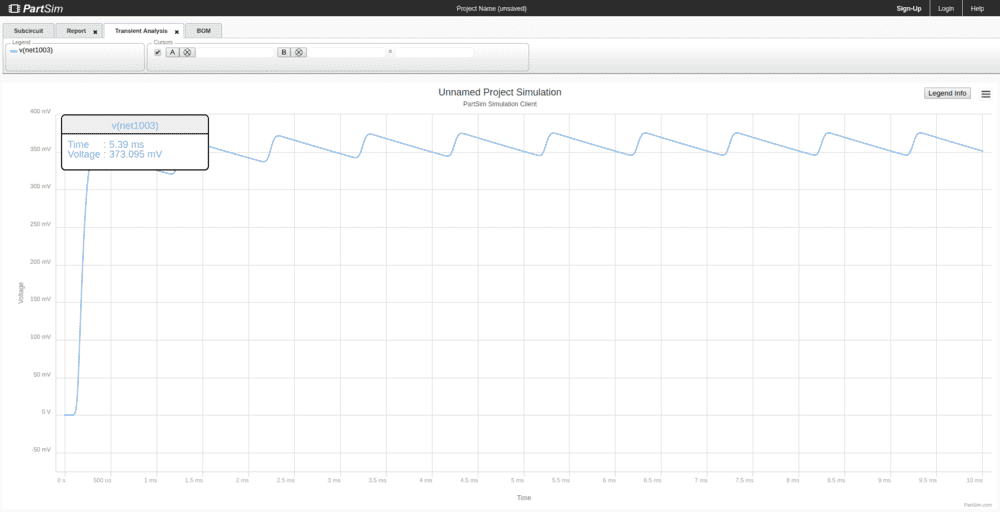

And the output, as expected, is this "rippled DC" voltage:

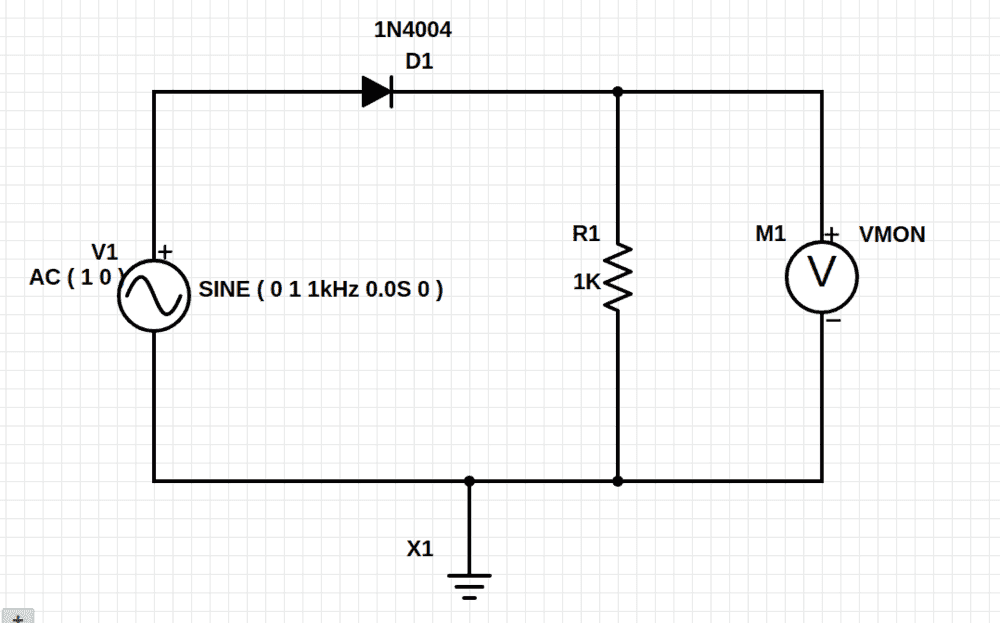

Alright. My issue is if we take a step back and get the voltage output of the circuit without the reservoir capacitor, like so (slightly different diode but shouldn't change anything):

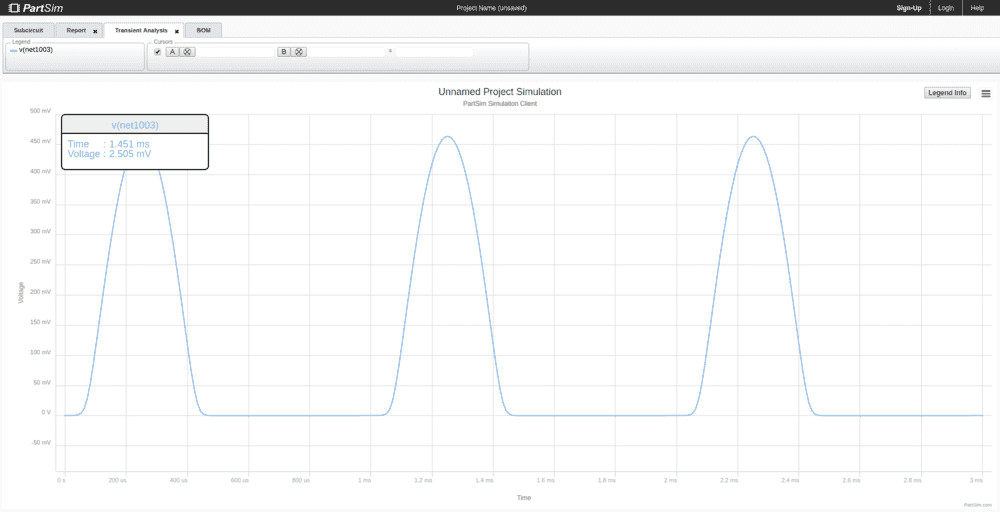

The output, as you would expect, would be a half-rectified sine wave:

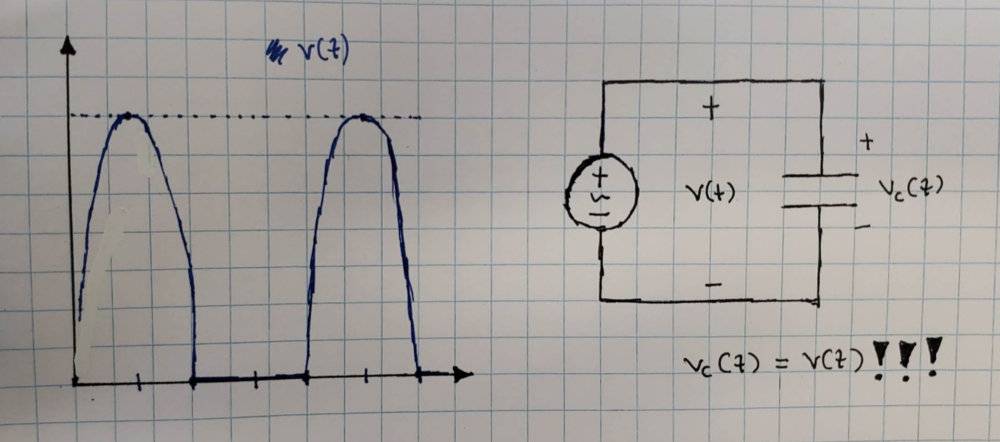

So, where is the link between the latter and former case! Most textbooks and literally everybody everywhere says that once the voltage source reaches peak, the capacitor will also be at peak minus the voltage drop across the diode, and then as the voltage source drops, it will become less than the capacitor's voltage and so the diode will become reverse-biased and that part of the circuit essentially gets disconnected until the voltage source rises back up again to meet back with the capacitor's voltage, and in the meantime the capacitor discharges its charge and maintains the slightly decreasing voltage across it. My issue is, why would the capacitor hold its voltage while the voltage source drops! It is a passive component. It should just follow the voltage as seen ^ in the latter case. For example, if I had this case:

You wouldn't expect the voltage across the capacitor to be that rippling DC of a half-wave rectifier. You would just expect it to follow the voltage source. It would be a contradiction violating KVL if the capacitor's voltage and the source's voltage differed! And also violate the idea that the capacitor is a passive component!

Of course, I know that the capacitor voltage will be that rippling DC, but my question is why? What analysis can show this? Where's the math or the model to show this, say to someone who wouldn't know that the output would be rippled DC?

And the output, as expected, is this "rippled DC" voltage:

Alright. My issue is if we take a step back and get the voltage output of the circuit without the reservoir capacitor, like so (slightly different diode but shouldn't change anything):

The output, as you would expect, would be a half-rectified sine wave:

So, where is the link between the latter and former case! Most textbooks and literally everybody everywhere says that once the voltage source reaches peak, the capacitor will also be at peak minus the voltage drop across the diode, and then as the voltage source drops, it will become less than the capacitor's voltage and so the diode will become reverse-biased and that part of the circuit essentially gets disconnected until the voltage source rises back up again to meet back with the capacitor's voltage, and in the meantime the capacitor discharges its charge and maintains the slightly decreasing voltage across it. My issue is, why would the capacitor hold its voltage while the voltage source drops! It is a passive component. It should just follow the voltage as seen ^ in the latter case. For example, if I had this case:

You wouldn't expect the voltage across the capacitor to be that rippling DC of a half-wave rectifier. You would just expect it to follow the voltage source. It would be a contradiction violating KVL if the capacitor's voltage and the source's voltage differed! And also violate the idea that the capacitor is a passive component!

Of course, I know that the capacitor voltage will be that rippling DC, but my question is why? What analysis can show this? Where's the math or the model to show this, say to someone who wouldn't know that the output would be rippled DC?

Attachments

-

Half-Wave Rectifier Circuit with Reservoir Capacitor.png17 KB · Views: 902

Half-Wave Rectifier Circuit with Reservoir Capacitor.png17 KB · Views: 902 -

Half-Wave Rectifier With 10uF Reservoir Capacitor.png12.1 KB · Views: 516

Half-Wave Rectifier With 10uF Reservoir Capacitor.png12.1 KB · Views: 516 -

Half-Wave Rectifier Circuit without Reservoir Capacitor.png13.5 KB · Views: 577

Half-Wave Rectifier Circuit without Reservoir Capacitor.png13.5 KB · Views: 577 -

Output on Half-Wave Rectifier Without Reservoir Capacitor.png15.2 KB · Views: 431

Output on Half-Wave Rectifier Without Reservoir Capacitor.png15.2 KB · Views: 431 -

Snapchat-1848085985.jpg40.7 KB · Views: 438

Snapchat-1848085985.jpg40.7 KB · Views: 438