- #1

dRic2

Gold Member

- 883

- 225

Hi,

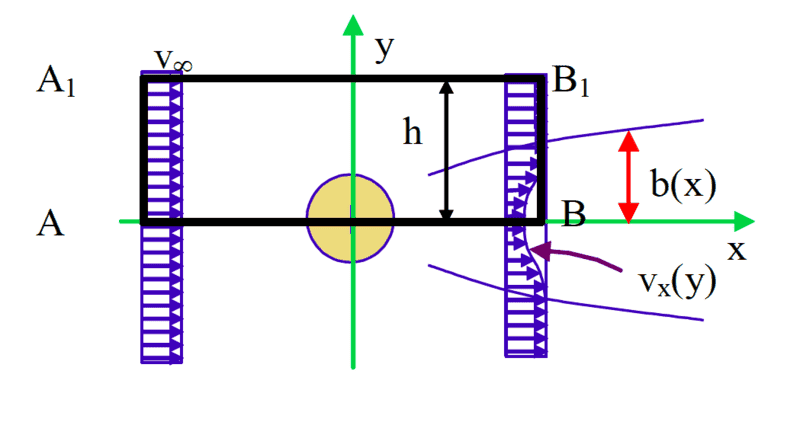

Let's consider a cylinder of infinite length and fluid flowing "over" (I'm not sure of which words I should use, sorry) it like in the figure:

Let's consider x>>D in order to neglect what's happening near the rear surface of the cylinder.

Let's get rid of static pressure which doesn't play a role here:

$$\nabla P = \nabla P_{s} + \nabla P_{d}$$

(where ##P_s## refers to static pressure while ##P_d## refers to dynamic pressure)

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau - \nabla P_{s} - \nabla P_{d} + \rho \mathbf g $$

Being ##\nabla P_s = -\rho \mathbf g##:

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau - \nabla P_{d} $$

Okay, now I found on a book that since x>>D the influence of the object on the flow is minimum so the small changes in the velocity profile suggest that ##\nabla P_{d} = 0##, obtaining the simplified equation:

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau $$

Well, it is not clear to me this last step. If ##\nabla P = 0## how is the fluid supposed to move?? Wouldn't ##\frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt}## and ##\nabla \tau## be ##0## as well (##0=0##)?

Let's consider a cylinder of infinite length and fluid flowing "over" (I'm not sure of which words I should use, sorry) it like in the figure:

Let's consider x>>D in order to neglect what's happening near the rear surface of the cylinder.

Let's get rid of static pressure which doesn't play a role here:

$$\nabla P = \nabla P_{s} + \nabla P_{d}$$

(where ##P_s## refers to static pressure while ##P_d## refers to dynamic pressure)

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau - \nabla P_{s} - \nabla P_{d} + \rho \mathbf g $$

Being ##\nabla P_s = -\rho \mathbf g##:

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau - \nabla P_{d} $$

Okay, now I found on a book that since x>>D the influence of the object on the flow is minimum so the small changes in the velocity profile suggest that ##\nabla P_{d} = 0##, obtaining the simplified equation:

$$ \frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt} = \nabla \tau $$

Well, it is not clear to me this last step. If ##\nabla P = 0## how is the fluid supposed to move?? Wouldn't ##\frac {D \mathbf v} {Dt}## and ##\nabla \tau## be ##0## as well (##0=0##)?