- #1

NatFex

- 26

- 3

This isn't a very technical series of questions, just some passing thoughts I had whilst looking over some notes I had on stellar parallax distancing.

Stellar parallax is always described as a means of "measuring the distance to stars." But from where?

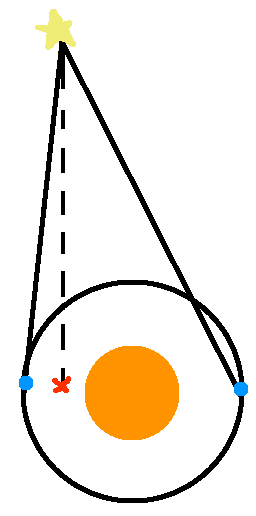

What I mean is, the distance, or the side of the right-angled triangle that's calculated is not a line joining the Earth and said star. It goes down from the star to some arbitrary point between the two positions of the Earth seen over a 6-month interval. If that wasn't clear I've made a drawing and stuck it in the spoiler below (see red 'x'):

Is this distance value typically adjusted later on in any way to make it more meaningful? If it is, what becomes the new reference point, since the Earth is constantly in motion? Is it the Sun?

Thanks

Stellar parallax is always described as a means of "measuring the distance to stars." But from where?

What I mean is, the distance, or the side of the right-angled triangle that's calculated is not a line joining the Earth and said star. It goes down from the star to some arbitrary point between the two positions of the Earth seen over a 6-month interval. If that wasn't clear I've made a drawing and stuck it in the spoiler below (see red 'x'):

Is this distance value typically adjusted later on in any way to make it more meaningful? If it is, what becomes the new reference point, since the Earth is constantly in motion? Is it the Sun?

Thanks

Last edited: