BilPrestonEsq said:

So are you for a fractional reserve system or a fixed money supply? That is the question.

This is a false choice - fractional reserve banking and a fixed money supply are not mutually exclusive. You continue to have a serious misunderstanding of elementary economic principle in these threads, and to disregard attempts to correct that misunderstanding.

Given that, there's little point in continuing any discussions with you on this subject.

Fractional reserve is impossible to sustain. IMPOSSIBLE.

Why? By what standard?

Every good and service provided on a market is provided on a fractional reserve basis. Is currency special, or are all markets "impossible to sustain", and by what accepted, conventional theory of economics is this true?

Look at the market for gasoline. The demand for gasoline is a function of the number of cars, the size of their tanks, and their mileage. This would be pretty simple to regress and estimate, and if we assume everybody starts from Full, you could state absolutely how much the demand for gasoline in the United States is per mile driven.

Now if you plotted this against the supply of gasoline per mile driven, you'd discover a (maybe shocking?) fact - the supply of gasoline in every tank at every service station in the nation at any given moment is a

fraction of the volume necessary to meet hypothetical peak demand. That is, if every car simultaneously decided to fill up its tanks, we would run out of gas.

Does this mean that the gasoline market is "unsustainable"? How about the sock, milk, corn, water, or TV markets - in each case, the situation is the same. The reason this is OK is because the demand for any product has an impulse. The impulse for gasoline consumption is, approximately, when you have an empty tank. Not everybody in the country has an empty tank at the same time - some people have half a tank, some 3/4, etcetera. Their demand for gasoline at the moment is zero, but their pent up demand is half a tank, or 1/4 of a tank, etcetera.

Currency is no different. In an average month, my expenses are approximately $4,000 after income taxes. That is, my monthly demand for currency is $4,000. Does that mean on Monday, January 31st I need $4,000 cash? Of course not - today I only bought lunch and a cup of coffee, and spent maybe $20. So my demand for currency on Monday the 31st was $20 cash, with ~$3,980 of pent up or already met demand. So my bank only needs to keep $20 on hand to meet my demand at that moment, and so on throughout the system, such that the volume of currency in all the vaults in the country at any given day can be less than average daily demand, as long as the U factor (the error term) averages out to zero in the long run.

Now, obviously it is impossible to accurately graph the demand function for currency for an economy of any realistic scale. However, this curve can be estimated using regression models, to reasonable degrees of accuracy. These models are used by banks to successfully project their currency needs in the same way that the gas station operator successfully projects how much gasoline he'll need in his tanks. Too much gas, and you've paid storage and capital costs that could have been deferred or eliminated; too little and you weren't able to meet demand, losing sales or forcing you to take emergency loans from somebody else (both costly propositions).

I understand the myth of fractional reserve banking introducing some kind of systemic risk is pervasive,

but this does not make it true. The myth that heavier objects accelerate faster due to gravity than lighter ones is also pervasive, and also untrue.

There is no systemic risk. In the event that the demand for currency exceeded projections and/or stocks, and banks were unable to meet it, currency values would rise relative to, say, bonds, until eventually people would be either unable or unwilling to consume additional units of currency. This is the same mechanism that makes sure there's enough milk on store shelves to go around without spoilage, and it works remarkably well such that aggregate surpluses and shortages are virtually unheard of in market economies over any meaningful term - this is a problem unique to planned economies.

Currency is no different; there has never been a market-induced currency crisis in countries with free floating exchange rates (defined as a radical change in currency values over short terms). These crises only happen when countries are trying to maintain a fixed or target exchange rate, and become unable to do so against market forces. When the state capitulates, the pent up change in value rapidly materializes as the currency moves quickly towards market equilibrium. See Mexico, Argentina, Thailand, and Russia in the '90s. Central banks in the States and elsewhere allow their currency values to float with market tides, acting instead to smooth out or stabilize the swings in either currency values or the broader macroeconomy, instead of trying to maintain a fixed target rate environment for precisely this reason.

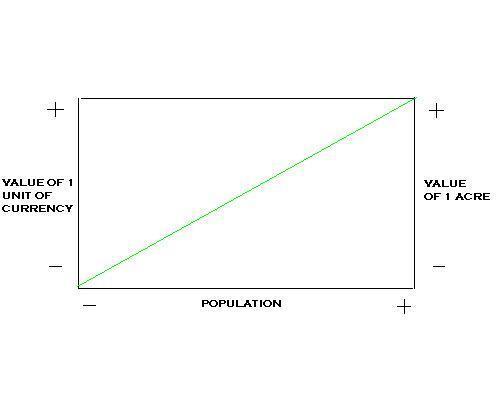

Finally, it does not follow that a fixed supply of currency would be preferable to a liquid supply. If the supply were fixed, as you rightly point out, a rising population would increase its value. So would a growing economy. This would necessitate a higher velocity of money, which would increase the demand for financial infrastructure to facilitate the rapid movement of money from where it wasn't needed to places it was needed. If you believe that this kind of financial environment is more risky than one with less demand for the movement of currency between parties, then a fixed currency regime is precisely the opposite direction you'd want to move in. The alternative is insufficient currency to complete all demanded transactions in the economy, which stalls growth (if the transactions simply don't happen) and/or incetivizes a movement away from the currency as the basis of trade (if the parties find another means of making the trade) - a profit maximizing option for the individuals involved at the moment but something much less efficient in aggregate than a healthy and reliable currency exchange system.