Hamiltonian

- 296

- 193

- TL;DR

- -

Drago rule states that if –

Drago's rule was introduced to explain why the bond angles of molecules such as ##PH_3##, ##AsH_3##, ##SbH_3## differ so much from ##109^o28'## which is supposed to be the ideal bond angle of molecules with ##sp^3## hybridization(as the steric number ##Z = 4##). Is the fact that Dragos rule exists prove somewhat the failure of hybridization theory as the theory itself predicts the bond angles to be ##109^o28'## but in actuality, the bond angles are closer to ##90^o## hence implying hybridization does not take place?

The theory of hybridization does not account for the bond angles of these elements to be (##\approx 90^o##) and Dragos rule was born out of only experimental data.

The only theoretical proof that I have found that predicts Dragos rule is

(https://madoverchemistry.com/2018/1...l-bonding-24-covalent-bonding23-drago-rule-2/)

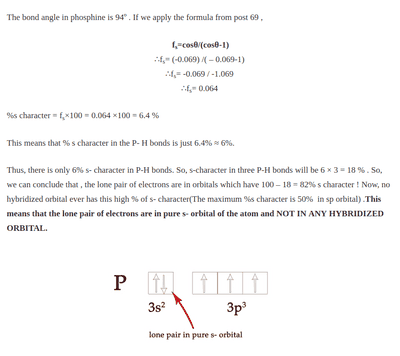

I am unclear as to how they get those equations(I can't find post 69 but I suspect its an equation from orbital analysis but I am not too sure) here it is proving by contradiction that no hybridization is going to take place in phosphine(##PH_3##) instead of solely relying on experimental data.

so in short I don't understand:

1. the theoretical prediction of Dragos rule(which is given in the link above) using orbital analysis.

2. If the fact that Dragos rule exists proves the failure of hybridization theory.

- the central atom has at least one lone pair of electron on it

- the central atom belongs to group 13,14,15 or 16 and is from the 3rd to 7th period.

- if electronegativity of the central element is 2.5 or less

- no. of sigma bonds+ lone pair=4

Drago's rule was introduced to explain why the bond angles of molecules such as ##PH_3##, ##AsH_3##, ##SbH_3## differ so much from ##109^o28'## which is supposed to be the ideal bond angle of molecules with ##sp^3## hybridization(as the steric number ##Z = 4##). Is the fact that Dragos rule exists prove somewhat the failure of hybridization theory as the theory itself predicts the bond angles to be ##109^o28'## but in actuality, the bond angles are closer to ##90^o## hence implying hybridization does not take place?

The theory of hybridization does not account for the bond angles of these elements to be (##\approx 90^o##) and Dragos rule was born out of only experimental data.

The only theoretical proof that I have found that predicts Dragos rule is

(https://madoverchemistry.com/2018/1...l-bonding-24-covalent-bonding23-drago-rule-2/)

I am unclear as to how they get those equations(I can't find post 69 but I suspect its an equation from orbital analysis but I am not too sure) here it is proving by contradiction that no hybridization is going to take place in phosphine(##PH_3##) instead of solely relying on experimental data.

so in short I don't understand:

1. the theoretical prediction of Dragos rule(which is given in the link above) using orbital analysis.

2. If the fact that Dragos rule exists proves the failure of hybridization theory.

Last edited: