kaigoss69

- 4

- 1

- TL;DR

- Is it possible to graduate the amount of air low and/or vacuum level inside a vacuum chamber

Hi there. I would like to start saying that I am not an engineer or scientist, and that my knowledge about vacuum and vacuum systems, in general, is limited, and I would like to apologize in advance if I am not describing the problem accurately.

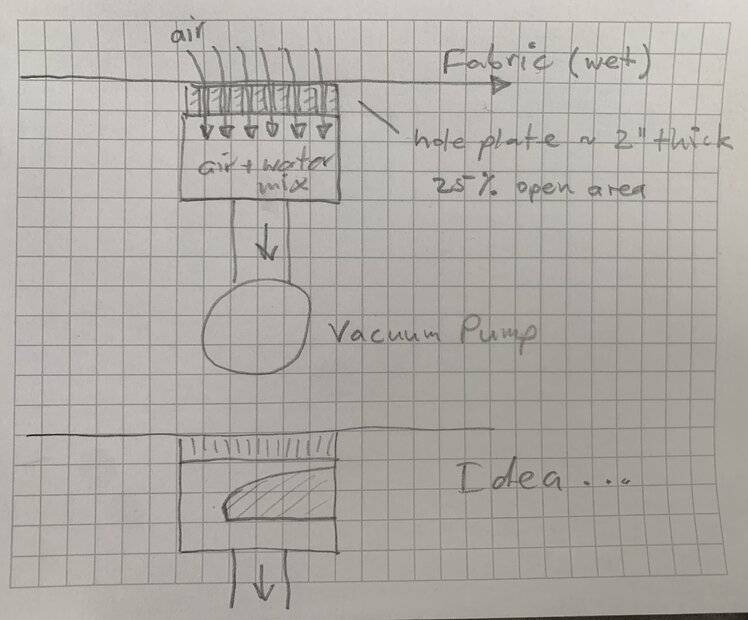

The application I am posing this question about is very simply, and amateurly, depicted in the attached sketch. I will try my best to describe it as follows:

In the industry, a continuous wet fabric belt, for this example 100 inches wide, is running over a series of vacuum boxes for the purpose of removing water from the fabric. The vacuum box in question, for this example, is 12 inches wide, in the direction of the fabric run, and spanning 100 inches across. On top of the vacuum box sits a thick metal plate, that is perforated with small holes. The hole diameters are 1/4" and the holes are evenly spaced, yielding 25% open area. The thickness of the plate is 2". This design cannot be changed.

The vacuum chamber has a depth of at least 5x the thickness of the plate, so in this case 10". The vacuum chamber is connected, via piping, to a vacuum pump. The typical level of vacuum inside the vacuum chamber is -60 kPa. The fabric traverses over the vacuum chamber at 50 mph.

The dewatering process is dependent mainly on air flow through the fabric, meaning the more air flow, the higher the dewatering rate. The objective of the process is to get the fabric as dry as possible, but the fabric is sensitive to "damage" from water flow, and it has been shown that using a number of these vacuum chambers in series, each one with a slightly higher vacuum load applied, creates the best results. So, for example, there would be 5 vacuum chambers in series, with vacuum loads starting at 20 kPa, and increasing 10 kPa per chamber, resulting in 60 kPa in the last chamber. The last 3 vacuum chambers have 40, 50 and 60 kPa vacuum, respectively.

Since the use of multiple chambers requires multiple vacuum pumps, my "idea" is to combine the graduation of vacuum (and/or air flow) in one single chamber.

Now here is my question: Is it possible to "graduate" the vacuum level (and/or air flow) from the beginning (left side) to the end (right side) of the chamber, with the introduction of some sort of obstacle, in this case a curved "plate" as depicted in the sketch? If not, is there another way to do it? - My theory is that the air flow inside the chamber would increase towards the end, and therefore creating more "drag", resulting in more air flow through the fabric near the end of the box, compared to the beginning of it.

This may very well be a stupid question, and totally outside the realm of possibility, but I have to ask...thanks in advance for the valuable insight and advice from this community.

The application I am posing this question about is very simply, and amateurly, depicted in the attached sketch. I will try my best to describe it as follows:

In the industry, a continuous wet fabric belt, for this example 100 inches wide, is running over a series of vacuum boxes for the purpose of removing water from the fabric. The vacuum box in question, for this example, is 12 inches wide, in the direction of the fabric run, and spanning 100 inches across. On top of the vacuum box sits a thick metal plate, that is perforated with small holes. The hole diameters are 1/4" and the holes are evenly spaced, yielding 25% open area. The thickness of the plate is 2". This design cannot be changed.

The vacuum chamber has a depth of at least 5x the thickness of the plate, so in this case 10". The vacuum chamber is connected, via piping, to a vacuum pump. The typical level of vacuum inside the vacuum chamber is -60 kPa. The fabric traverses over the vacuum chamber at 50 mph.

The dewatering process is dependent mainly on air flow through the fabric, meaning the more air flow, the higher the dewatering rate. The objective of the process is to get the fabric as dry as possible, but the fabric is sensitive to "damage" from water flow, and it has been shown that using a number of these vacuum chambers in series, each one with a slightly higher vacuum load applied, creates the best results. So, for example, there would be 5 vacuum chambers in series, with vacuum loads starting at 20 kPa, and increasing 10 kPa per chamber, resulting in 60 kPa in the last chamber. The last 3 vacuum chambers have 40, 50 and 60 kPa vacuum, respectively.

Since the use of multiple chambers requires multiple vacuum pumps, my "idea" is to combine the graduation of vacuum (and/or air flow) in one single chamber.

Now here is my question: Is it possible to "graduate" the vacuum level (and/or air flow) from the beginning (left side) to the end (right side) of the chamber, with the introduction of some sort of obstacle, in this case a curved "plate" as depicted in the sketch? If not, is there another way to do it? - My theory is that the air flow inside the chamber would increase towards the end, and therefore creating more "drag", resulting in more air flow through the fabric near the end of the box, compared to the beginning of it.

This may very well be a stupid question, and totally outside the realm of possibility, but I have to ask...thanks in advance for the valuable insight and advice from this community.