Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around deriving the formula for kinetic energy using calculus. Participants explore various mathematical steps and concepts involved in the derivation, including the use of Cartesian coordinates, vector notation, and the application of the chain rule.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Mathematical reasoning

- Debate/contested

Main Points Raised

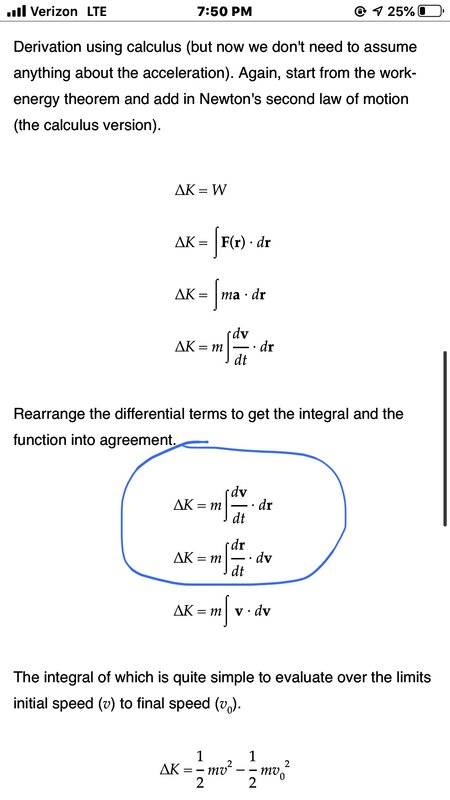

- One participant expresses confusion about switching the positions of variables in the derivation, specifically regarding the notation used for velocity and position vectors.

- Another participant suggests expressing the derivative of velocity in terms of Cartesian components and provides a detailed breakdown using the chain rule.

- A later reply questions the clarity of rewriting the expression in Cartesian coordinates and seeks further explanation on the process.

- Some participants discuss the implications of using different coordinate systems (Cartesian, cylindrical, spherical) for representing position vectors and their components.

- One participant critiques a previous statement about coordinate systems, emphasizing that the representation of position vectors differs based on the chosen basis.

- Another participant introduces an integral approach to the derivation, discussing the relationship between work and kinetic energy through line integrals and Newton's laws.

- One participant summarizes the derivation of the work-energy theorem, linking it to the definition of kinetic energy.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the appropriate coordinate systems to use and the implications of switching variables in the derivation. The discussion remains unresolved regarding the best approach to represent the derivation accurately.

Contextual Notes

Participants highlight the importance of consistency in coordinate systems when discussing vector representations. There are also mentions of potential complications in integration due to the non-monotonic nature of variables along certain paths.