Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Andrew Browder's book: "Mathematical Analysis: An Introduction" ... ...

I am currently reading Chapter 3: Continuous Functions on Intervals and am currently focused on Section 3.1 Limits and Continuity ... ...

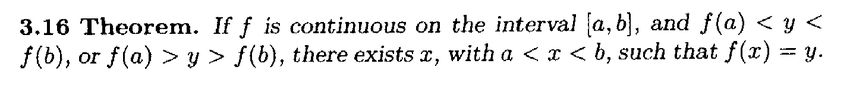

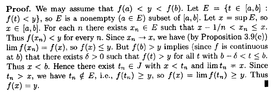

I need some help in understanding the proof of Theorem 3.16 ...Theorem 3.16 and its proof read as follows:

View attachment 9549

View attachment 9550

In the above proof by Andrew Browder we read the following:

" ... ... But $$f(b) \gt y$$ implies (since $$f$$ is continuous at $$b$$) that there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that $$f(t) \gt y$$ for all $$t$$ with $$b - \delta \lt t \leq b$$. ... ... "My question is as follows:

How do we demonstrate explicitly and rigorously that since $$f$$ is continuous at $$b$$ and $$f(b) \gt y $$ therefore we have that there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that $$f(t) \gt y$$ for all $$t$$ with $$b - \delta \lt t \leq b$$. ... ... Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

***NOTE***

The relevant definition of one-sided continuity for the above is as follows:

$$f$$ is continuous from the left at $$b$$ implies that for every $$\epsilon \gt 0$$ there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that for all $$x \in [a, b]$$ ...

we have that $$b - \delta \lt x \lt b \Longrightarrow \mid f(x) - f(b) \mid \lt \epsilon$$

I am currently reading Chapter 3: Continuous Functions on Intervals and am currently focused on Section 3.1 Limits and Continuity ... ...

I need some help in understanding the proof of Theorem 3.16 ...Theorem 3.16 and its proof read as follows:

View attachment 9549

View attachment 9550

In the above proof by Andrew Browder we read the following:

" ... ... But $$f(b) \gt y$$ implies (since $$f$$ is continuous at $$b$$) that there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that $$f(t) \gt y$$ for all $$t$$ with $$b - \delta \lt t \leq b$$. ... ... "My question is as follows:

How do we demonstrate explicitly and rigorously that since $$f$$ is continuous at $$b$$ and $$f(b) \gt y $$ therefore we have that there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that $$f(t) \gt y$$ for all $$t$$ with $$b - \delta \lt t \leq b$$. ... ... Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

***NOTE***

The relevant definition of one-sided continuity for the above is as follows:

$$f$$ is continuous from the left at $$b$$ implies that for every $$\epsilon \gt 0$$ there exists $$\delta \gt 0$$ such that for all $$x \in [a, b]$$ ...

we have that $$b - \delta \lt x \lt b \Longrightarrow \mid f(x) - f(b) \mid \lt \epsilon$$