- #1

nil1996

- 301

- 7

Meaning of poem "Suburbs"

Hello PF :

:

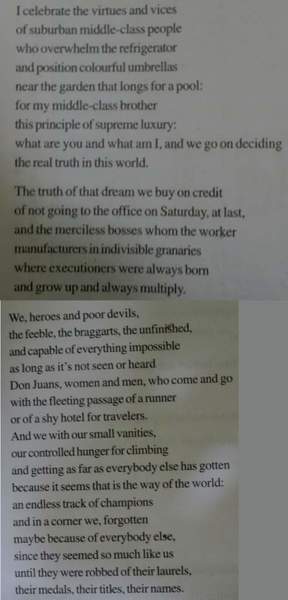

I have the following poem named Suburbs by Pablo Neruda.The poem is getting very hard for me to understand.

i have understood it as:

the poet says that he likes the good and bad things of the middle class people who just overpower refrigerator(things that make people proud).

Not understood the meaning of ""position colorful ...for pool:""

Hello PF

I have the following poem named Suburbs by Pablo Neruda.The poem is getting very hard for me to understand.

i have understood it as:

the poet says that he likes the good and bad things of the middle class people who just overpower refrigerator(things that make people proud).

Not understood the meaning of ""position colorful ...for pool:""