Enigman said:

For the claim Neruda don't do political poems...

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/454550.Spain_in_Our_Hearts_Espana_En_El_Corazon

He did both surrealist (cat, dog and apples) and overtly political manifestoes (this, Canto, Explaining,oranges)

Amazon doesn't offer a look into that book, so I can't see if I'd call what's in it "political." This is what I consider political:

Arise, children of the Fatherland

The day of glory has arrived!

Tyranny's bloody banner

Is raised against us.

Do you hear, in the countryside,

The roar of those ferocious soldiers?

They're coming right into your arms

To cut the throats of your sons and women! etc. etc.

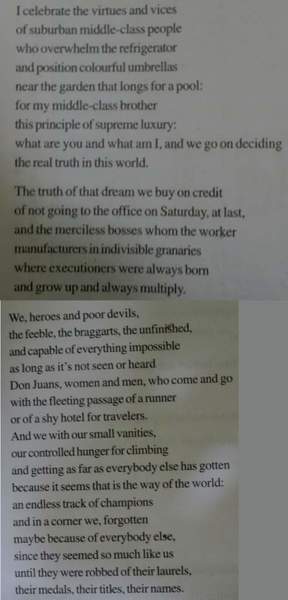

This, by Neruda, on the other hand is a human poem:

The Dictators

An odor has remained among the sugarcane:

a mixture of blood and body, a penetrating

petal that brings nausea.

Between the coconut palms the graves are full

of ruined bones, of speechless death-rattles.

The delicate dictator is talking

with top hats, gold braid, and collars.

The tiny palace gleams like a watch

and the rapid laughs with gloves on

cross the corridors at times

and join the dead voices

and the blue mouths freshly buried.

The weeping cannot be seen, like a plant

whose seeds fall endlessly on the earth,

whose large blind leaves grow even without light.

Hatred has grown scale on scale,

blow on blow, in the ghastly water of the swamp,

with a snout full of ooze and silence

The difference being that the former is lurid two dimensional demagoguery conceived purely for political purposes, and the latter is a three dimensional work of art. The political message in the latter does not take precedence over the art the way it does in the former and in, say, the plays and song lyrics of Bertold Brecht*. The latter is a human poem by a human poet outraged by a political situation.

So, I would like to see something considered unequivocally political by him to see whether he descends into demagoguery or indoctrination, or maintains his poetic standard.

Neruda often used 'I' to denote the whole of common people, here he's just using 'we' in the same sense.

If he used "I" to denote the whole of common people, it would mean he identified with them, no? Likewise with "we".

For the rest:

Seems to be too old an debate to be resolved today:

In an essay entitled "Pablo Neruda and Verdadismo " Stephen Hart says; "Critics, of course, routinely split Neruda's work into two halves: on the one hand there is the pre-political poetry (1924-37) and, on the other, the committed poetry (1937-73)" (256). Greg Dawes* says the following about this split in criticism: "Two very different groups of critics wrote on Neruda's work from the 1940s to the 1980s. The first group concentrated primarily on poetic form and either ignored Neruda's politics or did not consider the well-known attraction to Marxism among the intellectuals and artists of Neruda's generation" (26). Critics focused on poetic form primarily discuss Neruda's earlier work like Twenty Poems of Love and Residence land II. The critics concerned with the historical and Marxist influences tend to focus on Canto General written in 1950.

http://www.skachate.com/docs/index-525488.html

*From Dawes, Greg. Verses Against the Darkness: Pablo Neruda's Poetry and Politics. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2006.

It would seem to me the fact his politics is so ignorable by critics is because the fineness of his poetry trumps the message. Brecht (see below) did a lot of weird experimentation to find ways to sort of

kill the art of his plays so the audience would only hear the message. Brecht was primarily a political agitator and theater was a mere vehicle for that.

*"From his late twenties Brecht remained a lifelong committed Marxist who, in developing the combined theory and practice of his "epic theatre", synthesized and extended the experiments of Erwin Piscator and Vsevolod Meyerhold to explore the theatre as a forum for political ideas and the creation of a critical aesthetics of dialectical materialism.

Epic Theatre proposed that a play should not cause the spectator to identify emotionally with the characters or action before him or her, but should instead provoke rational self-reflection and a critical view of the action on the stage. Brecht thought that the experience of a climactic catharsis of emotion left an audience complacent. Instead, he wanted his audiences to adopt a critical perspective in order to recognise social injustice and exploitation and to be moved to go forth from the theatre and effect change in the world outside. For this purpose, Brecht employed the use of techniques that remind the spectator that the play is a representation of reality and not reality itself. By highlighting the constructed nature of the theatrical event, Brecht hoped to communicate that the audience's reality was equally constructed and, as such, was changeable." -Wiki

He coached his actors, for instance, to alienate the audience with a kind of artificial acting style he called, "alienated acting." He

didn't want them sucked into the story, or to be able to forget they were watching a play.

That, to me, is the epitome of a political artist: someone who whores the medium out to indoctrinate. I don't get this vibe from Neruda at all, nor do I see a demagogue.

:

: