Aaron121

- 15

- 1

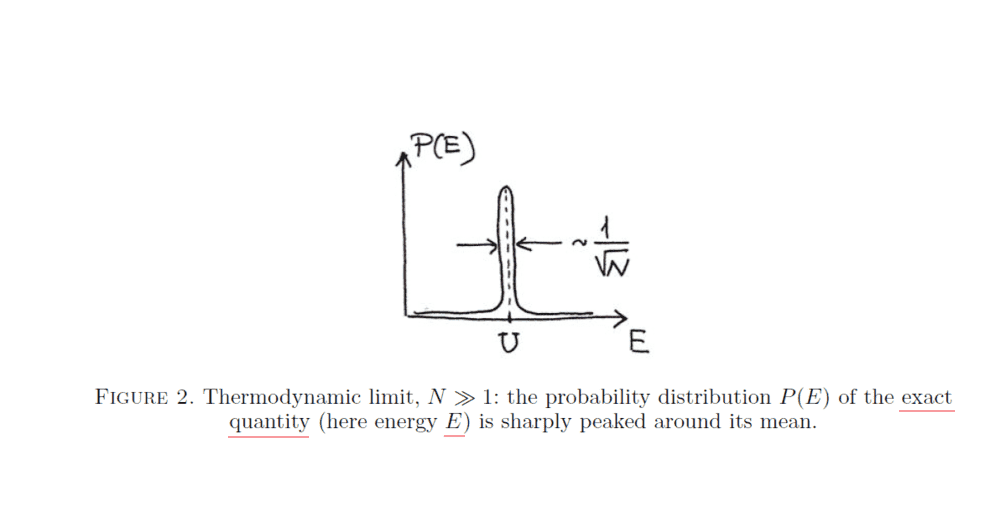

In these lecture notes about statistical mechanics, page ##10##, we can see the graph below.

It represents the distribution (probability density function) of the kinetic energy ##E## (a random variable) of all the gas particles (i.e., ##E=\sum_{i}^{N} E_{i}##, where ##E_{i}## (also a random variable) is the kinetic energy of gas molecule ##i##, and ##N## is the total number of gas molecules). ##U## above is the mean value of ##E## (##U=\langle E\rangle##).

The author claims that the width of the distribution above is approximately ##\frac{\sigma _{E}}{\langle E\rangle}=\frac{\langle (E-\textrm {U})^{2} \rangle ^{1/2}}{\langle E\rangle}##. Where does this approximation come from? Shouldn't it be just ##\sigma _{E}=\langle (E-\textrm {U})^{2} \rangle ^{1/2}##?

The exact quote reads,

##\Delta E_{rms}## above is just ##\sigma _{E}##.

It represents the distribution (probability density function) of the kinetic energy ##E## (a random variable) of all the gas particles (i.e., ##E=\sum_{i}^{N} E_{i}##, where ##E_{i}## (also a random variable) is the kinetic energy of gas molecule ##i##, and ##N## is the total number of gas molecules). ##U## above is the mean value of ##E## (##U=\langle E\rangle##).

The author claims that the width of the distribution above is approximately ##\frac{\sigma _{E}}{\langle E\rangle}=\frac{\langle (E-\textrm {U})^{2} \rangle ^{1/2}}{\langle E\rangle}##. Where does this approximation come from? Shouldn't it be just ##\sigma _{E}=\langle (E-\textrm {U})^{2} \rangle ^{1/2}##?

The exact quote reads,

the distribution of the system's total energy ##E## (which is a random variable because particle velocities are random variables) is very sharply peaked around its mean ##U=\langle E\rangle##: the width of this peak is ##\sim \Delta E_{rms}/U \sim \frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}## . This is called the thermodynamic limit— the statement that mean quantities for systems of very many particles approximate extremely well the exact properties of the system.

##\Delta E_{rms}## above is just ##\sigma _{E}##.

Attachments

Last edited: