Re: Prove: 1^3+3^3+5^3+7^3+...+T^3=

Do you think this is fascinating too :

$$\sum_{d|n} \tau(d)^3 = \left [ \sum_{d|n} \tau(d) \right ]^2$$

or

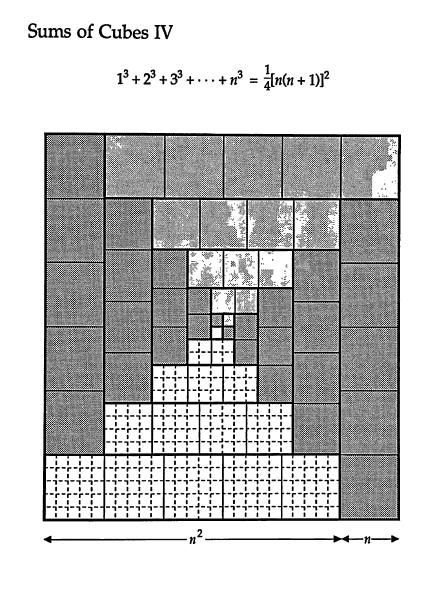

$$\sum_{k = 1}^n n^3 = \left [ \sum_{k = 1}^n n \right ]^2$$

And if you do, how about the multisets

$$\{1, 2, 2, 3, 5\}, \{3, 3, 3, 3, 6\}, \text{etc}$$

with the same property but in neither of the three classes, including the one you've given above. Also, [Hold you chair and don't freak out!]

$$\bigg \{\frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, \frac23, 2, 2, 10 \bigg\}$$

$$\{1 + 11678679130451250771390i, 10114032809617941274227 + 5839339565225625385695i\}$$

They have some strange properties, mostly of number theoretic interest, although there might be something for you here :

$$\{1, 2, 3\} \otimes \{1, 2\} = \{1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 6\}$$

This operation forms a semigroup.

PS : All of these are recorded in MMF in 5 topics : http://www.mymathforum.com/viewtopic.php?f=40&t=37609, http://www.mymathforum.com/viewtopic.php?f=40&t=40594, http://www.mymathforum.com/viewtopic.php?f=40&t=40612, http://www.mymathforum.com/viewtopic.php?f=40&t=41547, http://www.mymathforum.com/viewtopic.php?f=40&t=41825 [read by order].