Murilo T

- 12

- 7

- Homework Statement

- A block is placed on a plane inclined at an angle θ. The coefficient of friction between the block and the plane is µ = tan θ. The block initially moves horizontally along the plane at a speed V . In the long-time limit, what is the speed of the block?

- Relevant Equations

- ms˙ϕ˙ = mg sin θ cos ϕ

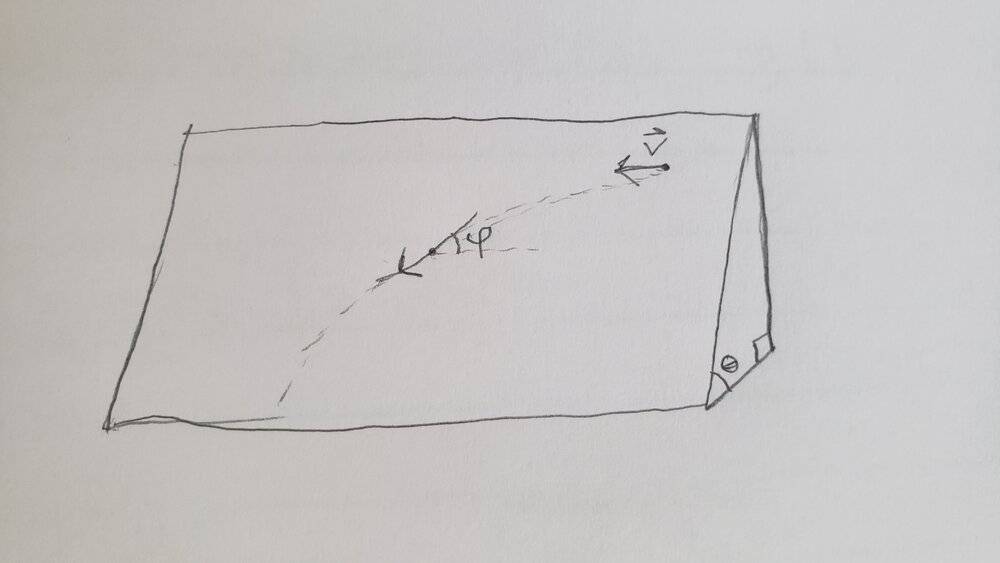

This question is from the David Morin ( Classical Mechanics ) - problem 3.7. I spent some time trying to figure it out the solution by myself, but since I couldn't, I looked into the solution in the book, but I got even more lost. So I searched for an online solution that could help me at least visualize the problem, and I found two solutions here, one here, and some one that already asked the same question here. There isn't any pictures of the problem anywhere, so this is my interpretation:

I get that the forces down the plane cancels out, and the equation for the acceleration in the tangential direction: m(ds^2/dt^2) = mg sinθ (sinϕ − 1).

But in the equation for the acceleration in the normal direction: m(ds/dt)(dϕ/dt) = mg sinθcosϕ, why the normal acceleration is (ds/dt)(dϕ/dt)?

And why the acceleration in the y-axis equals the negative acceleration in the tangetial direction?

I get that the forces down the plane cancels out, and the equation for the acceleration in the tangential direction: m(ds^2/dt^2) = mg sinθ (sinϕ − 1).

But in the equation for the acceleration in the normal direction: m(ds/dt)(dϕ/dt) = mg sinθcosϕ, why the normal acceleration is (ds/dt)(dϕ/dt)?

And why the acceleration in the y-axis equals the negative acceleration in the tangetial direction?