Soren4

- 127

- 2

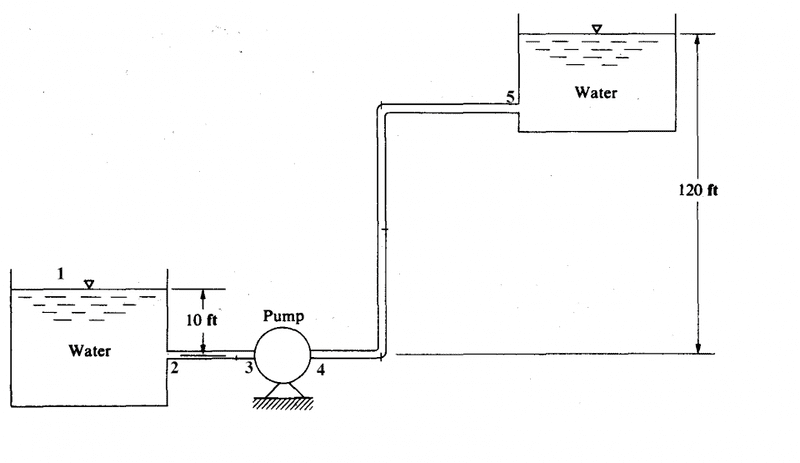

I have a doubt on the use of Bernoulli equation for pumps. Consider the situation in the picture.

I marked different points: ##1## on the surface of first tank, ##2## in the exit from first tank, ##3## just before the pump, ##4## just after the pump and ##5## entering the second tank.

Now consider Bernoulli equation in the "normal form" (ignoring the pump)

$$p_a+\frac{1}{2} \rho v_a^2 +\rho g h_a=p_b +\frac{1}{2} \rho v_b^2 +\rho g h_b\tag{1}$$

And in the form for the presence of pump delivering power ##\mathscr{P}##

$$(p_a+\frac{1}{2} \rho v_a^2 +\rho g h_a) Q +\mathscr{P}=(p_b +\frac{1}{2} \rho v_b^2 +\rho g h_b) Q \tag{2}$$

##a## and ##b## are two generic points among the ones listed above.

My question now is: can I use ##(2)## between any point before the pump and any point after the pump, regardless the height, velocity and pressure in such points?

I have this doubt because usually one takes point ##1## and ##5## and uses ##(2)## - and I'm ok with that- but, if the answer to previous question is yes, I could also choose to use ##(2)## between ##1## and ##4## or ##2## and ##5## or ##2## and ##3## and so on and that sound strange because the quantity ##p+\frac{1}{2} \rho v^2 +\rho g h## should be the same before and after the pump, indipendently from the particular point chosen. In other words I should be able to use ##(1)##, normal Bernoulli equation, between ##1## and ##2##, which is not very realistic, since the fluid in ##2## will probably move with a velocity that is influenced by the pump.

That is, even if ##2## is before the pump, the velocity there is different from the situation with no pump. And that's what I cannot understand here. How is that possible? And can I use ##(1)## between ##1## and ##2##?

Any suggestion is highly appreciated.

I marked different points: ##1## on the surface of first tank, ##2## in the exit from first tank, ##3## just before the pump, ##4## just after the pump and ##5## entering the second tank.

Now consider Bernoulli equation in the "normal form" (ignoring the pump)

$$p_a+\frac{1}{2} \rho v_a^2 +\rho g h_a=p_b +\frac{1}{2} \rho v_b^2 +\rho g h_b\tag{1}$$

And in the form for the presence of pump delivering power ##\mathscr{P}##

$$(p_a+\frac{1}{2} \rho v_a^2 +\rho g h_a) Q +\mathscr{P}=(p_b +\frac{1}{2} \rho v_b^2 +\rho g h_b) Q \tag{2}$$

##a## and ##b## are two generic points among the ones listed above.

My question now is: can I use ##(2)## between any point before the pump and any point after the pump, regardless the height, velocity and pressure in such points?

I have this doubt because usually one takes point ##1## and ##5## and uses ##(2)## - and I'm ok with that- but, if the answer to previous question is yes, I could also choose to use ##(2)## between ##1## and ##4## or ##2## and ##5## or ##2## and ##3## and so on and that sound strange because the quantity ##p+\frac{1}{2} \rho v^2 +\rho g h## should be the same before and after the pump, indipendently from the particular point chosen. In other words I should be able to use ##(1)##, normal Bernoulli equation, between ##1## and ##2##, which is not very realistic, since the fluid in ##2## will probably move with a velocity that is influenced by the pump.

That is, even if ##2## is before the pump, the velocity there is different from the situation with no pump. And that's what I cannot understand here. How is that possible? And can I use ##(1)## between ##1## and ##2##?

Any suggestion is highly appreciated.