- #1

Phylosopher

- 139

- 26

Hello,I had a discussion with my professor. He tried to convince me but I couldn't understand the idea.

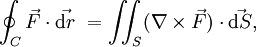

The Stokes Theorem (Curl Theorem) is the following:

My professor says that the value of the equation should be zero whenever the area of integration is closed! (which will make a volume in that sense!)

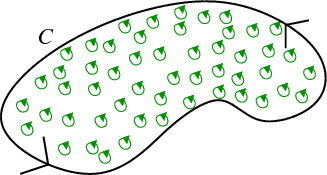

He tried to explain that if the area isn't closed then the current on the edge (closed path) of the shape can be represented thoroughly via a closed path integral without going into the whole let's say "infinitesimal currents inside the area"

Moreover, for a closed area there is no edge "closed path" where we can determine the current flow. Here is the problem, logically I find no answer to the problem sense there is no edges that contain the area, meanwhile he says the answer is zero which mean there is no flow.

Moreover, for a closed area there is no edge "closed path" where we can determine the current flow. Here is the problem, logically I find no answer to the problem sense there is no edges that contain the area, meanwhile he says the answer is zero which mean there is no flow.

Also, why can't we just chose a closed path on that closed area and find the answer from it

This might be a really basic "silly" question, I'm sorry but couldn't find any related thoughts in the web about Stokes' and Closed area.

The Stokes Theorem (Curl Theorem) is the following:

My professor says that the value of the equation should be zero whenever the area of integration is closed! (which will make a volume in that sense!)

He tried to explain that if the area isn't closed then the current on the edge (closed path) of the shape can be represented thoroughly via a closed path integral without going into the whole let's say "infinitesimal currents inside the area"

Also, why can't we just chose a closed path on that closed area and find the answer from it

This might be a really basic "silly" question, I'm sorry but couldn't find any related thoughts in the web about Stokes' and Closed area.