- #1

pepediaz

- 51

- 6

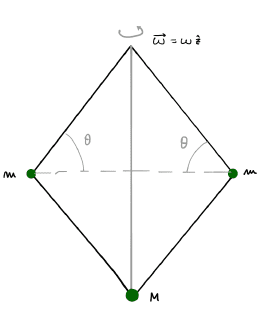

Summary:: not constant spin

How could I calculate the system lagrangian in function of the generalised coordinates and the conserved quantities associated to the system symmetries?

I've been struggling for the case with not constant angular velocity, but I don't realize what I have to do.

Thanks in advance

How could I calculate the system lagrangian in function of the generalised coordinates and the conserved quantities associated to the system symmetries?

I've been struggling for the case with not constant angular velocity, but I don't realize what I have to do.

Thanks in advance