- #1

fourthindiana

- 162

- 25

- TL;DR Summary

- When you use a multimeter to check for a short to ground on the compressor (or any other motor) on an air-conditioner, you are supposed to put one lead of the multimeter on one of the terminal spade of the compressor and hold the other lead of the multimeter to the metal casing of the air-conditioner to ground the lead out. I understand why you must attach one lead to one of the terminal spades of the compressor. But why does the other lead have to be attached to ground?

Back in December, I made a thread with a related topic as this titled "Ohm reading when there is a short in the condenser motor". But the question of this thread is distinct from the topic of my "Ohm reading when there is a short in the condenser motor" thread. Therefore, I have decided it would be best to create a new thread on this topic.

It's my understanding that a person can accurately check whether or not a compressor motor is shorted to ground in the following way: Hold one lead of the multimeter to ground. Then attach one lead of the multimeter to the common spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, that is an indication that the compressor is not shorted to ground. Keep one lead of the multimeter to ground, and attach the other lead of the multimeter to the start winding spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, the start winding is not shorted to ground. If there is a resistance reading less than infinite resistance, the start winding is shorted to ground. Then keep one lead of the multimeter to ground, and attach the other lead of the multimeter to the run winding spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, the run winding is not shorted to ground. If there is resistance less than infinite resistance, the run winding is shorted to ground.

In my thread "Ohm reading when there is a short in the condenser motor", PF member jim hardy told me that when a multimeter is set to a resistance scale, the multimeter actually directly measures not resistance but conductance. jim hardy said that the multimeter applies a modest voltage, typically 1.5 volts from its internal battery, and the multimeter measures the current that flows into the conductance of whatever I am measuring.

Zero current means no conductance which means infinite resistance.

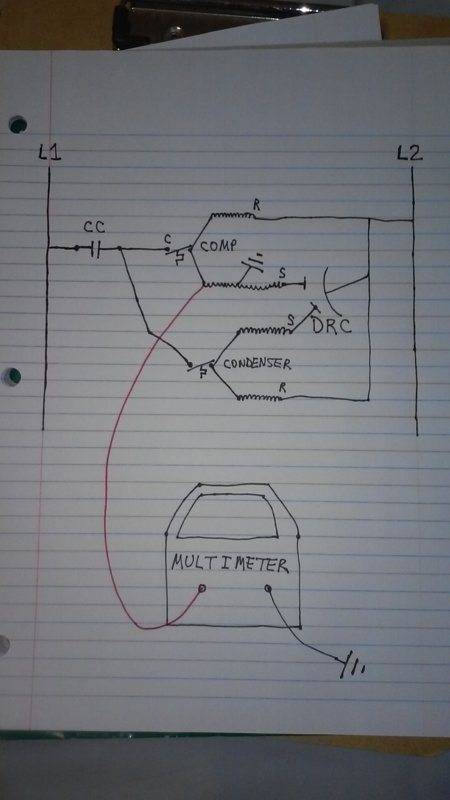

Below is a ladder diagram which shows my understanding of how a person would check for a short to ground:

I have seen videos on youtube in which HVAC technicians have checked for shorts to ground on compressors in air-conditioners, and the HVAC technicians always attached one lead of the multimeter to ground and then attached the other lead of the multimeter to a terminal spade of the compressor.

When an HVAC technician is checking for a short to ground on a compressor, I fully understand why the HVAC technician must attach one lead of the multimeter to one of the terminal spades of the compressor, but I don't fully understand why the HVAC technician must attach the other lead to ground. I understand that the multimeter measures resistance by applying a modest voltage from the multimeter's internal battery, and the multimeter measures the amount of current that flows into the conductance of whatever it is measuring.

Why does an HVAC technician have to have one lead of the multimeter attached to ground when checking for a short to ground on a compressor?

Does an HVAC technician have to have one lead of the multimeter attached to ground when checking for a short to ground on a compressor because having one lead of the multimeter attached to ground is necessary to have a complete circuit?

It's my understanding that a person can accurately check whether or not a compressor motor is shorted to ground in the following way: Hold one lead of the multimeter to ground. Then attach one lead of the multimeter to the common spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, that is an indication that the compressor is not shorted to ground. Keep one lead of the multimeter to ground, and attach the other lead of the multimeter to the start winding spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, the start winding is not shorted to ground. If there is a resistance reading less than infinite resistance, the start winding is shorted to ground. Then keep one lead of the multimeter to ground, and attach the other lead of the multimeter to the run winding spade of the compressor. If there is infinite resistance, the run winding is not shorted to ground. If there is resistance less than infinite resistance, the run winding is shorted to ground.

In my thread "Ohm reading when there is a short in the condenser motor", PF member jim hardy told me that when a multimeter is set to a resistance scale, the multimeter actually directly measures not resistance but conductance. jim hardy said that the multimeter applies a modest voltage, typically 1.5 volts from its internal battery, and the multimeter measures the current that flows into the conductance of whatever I am measuring.

Zero current means no conductance which means infinite resistance.

Below is a ladder diagram which shows my understanding of how a person would check for a short to ground:

I have seen videos on youtube in which HVAC technicians have checked for shorts to ground on compressors in air-conditioners, and the HVAC technicians always attached one lead of the multimeter to ground and then attached the other lead of the multimeter to a terminal spade of the compressor.

When an HVAC technician is checking for a short to ground on a compressor, I fully understand why the HVAC technician must attach one lead of the multimeter to one of the terminal spades of the compressor, but I don't fully understand why the HVAC technician must attach the other lead to ground. I understand that the multimeter measures resistance by applying a modest voltage from the multimeter's internal battery, and the multimeter measures the amount of current that flows into the conductance of whatever it is measuring.

Why does an HVAC technician have to have one lead of the multimeter attached to ground when checking for a short to ground on a compressor?

Does an HVAC technician have to have one lead of the multimeter attached to ground when checking for a short to ground on a compressor because having one lead of the multimeter attached to ground is necessary to have a complete circuit?