at570

I have a rather unusual problem and I want to understand the physics of it.

Imagine a car with a high center of gravity and front and back wheels close together.

It gets some speed and then brakes, and the front goes down.Just when it stops, and the load tranfer is done, there's no force from braking pushing the front down, only weight transfer from the center of gravity moving, specifically a line from the center of gravity straight down to the ground moving closer to the front wheels because of the rotation of the body, putting more of the cars weight on the front two wheels.

Is there ever a situation where it will stay in this position? It has springs and dampers on all 4 wheels and there's no damage. Also don't include fluids shifting due to inertia in weight transfer. What equations talk about this? Why do cars generally right themselves and return to level and not some other angle based on the center of gravity and the 4 spring forces?

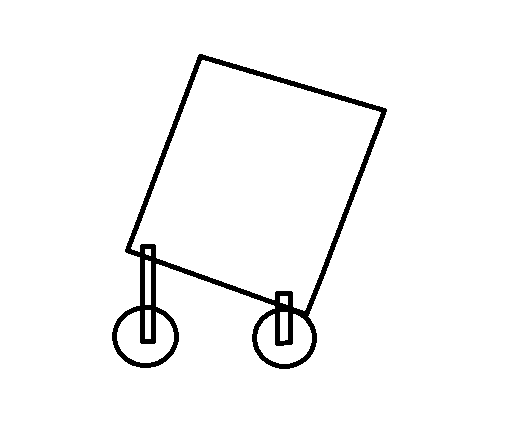

Heres a picture of the car and the position it could get stuck in.

I see 3 main things that would effect whether or not the car will do this, spring force or spring constant, center of gravity location, and distance between the front and back wheels. Basically, what equations talk about weight transfer overcoming the spring force? Can you possibly find the spring force or spring constant that is the threshold where this will start to happen? Or some other way? Please use equations. I think this has to do with spring systems. How would you go about solving this? What physics ideas would you use? I am really not sure how to come at this problem. Also, the springs are all the same, and the wheels are equal distance from the center of gravity when its vertical. Thanks

Imagine a car with a high center of gravity and front and back wheels close together.

It gets some speed and then brakes, and the front goes down.Just when it stops, and the load tranfer is done, there's no force from braking pushing the front down, only weight transfer from the center of gravity moving, specifically a line from the center of gravity straight down to the ground moving closer to the front wheels because of the rotation of the body, putting more of the cars weight on the front two wheels.

Is there ever a situation where it will stay in this position? It has springs and dampers on all 4 wheels and there's no damage. Also don't include fluids shifting due to inertia in weight transfer. What equations talk about this? Why do cars generally right themselves and return to level and not some other angle based on the center of gravity and the 4 spring forces?

Heres a picture of the car and the position it could get stuck in.

I see 3 main things that would effect whether or not the car will do this, spring force or spring constant, center of gravity location, and distance between the front and back wheels. Basically, what equations talk about weight transfer overcoming the spring force? Can you possibly find the spring force or spring constant that is the threshold where this will start to happen? Or some other way? Please use equations. I think this has to do with spring systems. How would you go about solving this? What physics ideas would you use? I am really not sure how to come at this problem. Also, the springs are all the same, and the wheels are equal distance from the center of gravity when its vertical. Thanks

.. And often half the businesses on our streets have to do with motorcar accessories. Thanks for commenting.

.. And often half the businesses on our streets have to do with motorcar accessories. Thanks for commenting. (rather rarely at least

(rather rarely at least  ). Thanks for commenting.

). Thanks for commenting.