Soren4

- 127

- 2

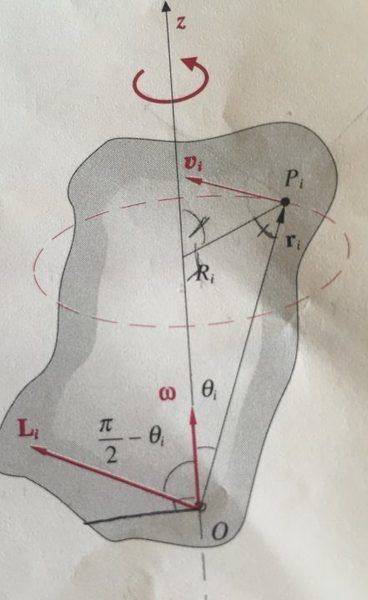

Consider the rotation of a rigid body about a fixed axis z, not passing through a principal axis of inertia of the body. The angular momentum \vec{L} has a parallel component to the z axis (called \vec{L_z}) and a component perpendicular to it (called \vec{L_n}). I have some doubts on \vec{L_n}.

From the picture we have that, taking a singular point of the rigid body P_i,

\mid \vec{L_{n,i}}\mid=m_i r_i R_i \omega cos\theta_i\implies \mid \vec{L_n}\mid=\omega \sum m_i r_i R_i cos\theta_i

Is this correct? Now the quantity \sum m_i r_i R_i cos\theta_i depends on the point O used for the calculation of momenta, nevertheless it is a costant quantity, once calculated, right?

So is it possible to say that \mid \vec{L_n}\mid \propto \mid \vec{\omega} \mid (1)?

If \vec{\omega} is constant then there is an external torque \vec{\tau}=\frac{d\vec{L}}{dt}=\frac{d\vec{L_n}}{dt}=\vec{\omega}\times\vec{L_n}, perpendicular both to \vec{\omega} and \vec{L_n}.

Now suppose that the direction of \vec{\omega} is still the same (the axis is fixed) but \mid\vec{\omega}\mid changes. Then the external torque has two components. For the component parallel to the axis we can write \vec{\tau_z}=\frac{d\vec{L_z}}{dt}=I_z \vec{\alpha}, once calculated the moment of inertia I_z with respect to the axis of rotation, while for the orthogonal component we have \vec{\tau_n}=\frac{d\vec{L_n}}{dt}, but what are the characteristics of the component \vec{L_n} in that case?

If (1) holds then \frac{d\mid \vec{L_n} \mid}{dt} \propto \mid \vec{\alpha} \mid

But what about the direction of \vec{L_n} and of its derivative?

From the picture we have that, taking a singular point of the rigid body P_i,

\mid \vec{L_{n,i}}\mid=m_i r_i R_i \omega cos\theta_i\implies \mid \vec{L_n}\mid=\omega \sum m_i r_i R_i cos\theta_i

Is this correct? Now the quantity \sum m_i r_i R_i cos\theta_i depends on the point O used for the calculation of momenta, nevertheless it is a costant quantity, once calculated, right?

So is it possible to say that \mid \vec{L_n}\mid \propto \mid \vec{\omega} \mid (1)?

If \vec{\omega} is constant then there is an external torque \vec{\tau}=\frac{d\vec{L}}{dt}=\frac{d\vec{L_n}}{dt}=\vec{\omega}\times\vec{L_n}, perpendicular both to \vec{\omega} and \vec{L_n}.

Now suppose that the direction of \vec{\omega} is still the same (the axis is fixed) but \mid\vec{\omega}\mid changes. Then the external torque has two components. For the component parallel to the axis we can write \vec{\tau_z}=\frac{d\vec{L_z}}{dt}=I_z \vec{\alpha}, once calculated the moment of inertia I_z with respect to the axis of rotation, while for the orthogonal component we have \vec{\tau_n}=\frac{d\vec{L_n}}{dt}, but what are the characteristics of the component \vec{L_n} in that case?

If (1) holds then \frac{d\mid \vec{L_n} \mid}{dt} \propto \mid \vec{\alpha} \mid

But what about the direction of \vec{L_n} and of its derivative?