Jackson Lee

- 77

- 1

I feel curious about why we pay so much attention on standing waves on the string. Doesn't transverse wave on the string can't be used to produce sound?

Transverse waves on a string can indeed produce sound, as demonstrated by their role in stringed musical instruments. While the sound generated in the air is longitudinal, transverse waves in the string can create these longitudinal waves. The discussion highlights the misconception that only standing waves produce sound, emphasizing that both standing and traveling waves contribute to sound generation. The filtering of non-resonant frequencies occurs due to the decay of higher harmonics, leaving primarily the fundamental mode audible.

PREREQUISITESMusicians, acoustics researchers, physics students, and anyone interested in the mechanics of sound production in stringed instruments.

But I have never seen anything about the topic since then, while nearly every physics books paid much attention on standing waves which surely could produce sound on string and wind instrument. Some of them even state clearly that it is standing waves that produce sound therefore we should make deep research into this topic. And I have found this description:[Those frequencies that are not one of the resonances are quickly filtered out—they are attenuated—and all that is left is the harmonic vibrations that we hear as a musical note.] How do them be filtered out?DaleSpam said:It certainly can be used to produce sound. That is how all stringed musical instruments work.

The wave that it creates in the air is longitudinal, but there is nothing preventing a transverse wave in the string from creating a longitudinal wave in the air.

Standing waves on the string are transverse waves. The standing pattern is created because there are (transverse) waves traveling in both directions up and down the string and reflecting back and forth between the ends.Jackson Lee said:But if transverse wave could also be used to produce sound, then why we make so much attention on standing waves instead of transverse waves?

Jackson Lee said:Thus, I felt surprisingly when watched that experiment.

DaleSpam said:It certainly can be used to produce sound. That is how all stringed musical instruments work.

olivermsun said:Camera artifacts aside, bowed strings are not filled with standing waves. There are clearly propagating transverse waves.

I'm not sure it's just semantic. If one is actually looking at some detailed waveforms or high-speed photography of a bowed string, then what one tends to see is a lot of "non ideal" phenomena.AlephZero said:This can turn into a debate about semantics. The same motion can be described either as a traveling wave reflected repeatedly from the ends of the string, or a superposition of standing waves of different frequencies (i.e integer multiples of the fundamental frequency). At an elementary level it's easiest to consider just one standing wave, which might explain why the OP's question.

Right. Because the realistic motion of the bowed string is actually pretty bizarre.On the other hand, a standard way to make a computer model of the physics of real string and wind instruments (rather than the idealized ones in a Physics 101 textbook) is to use "digital waveguide syntheses" which only uses transient waves.

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/swgt/

olivermsun said:I'm not sure it's just semantic. If one is actually looking at some detailed waveforms or high-speed photography of a bowed string, then what one tends to see is a lot of "non ideal" phenomena.

Maybe what I should have said is: "The motion of the bowed string isn't just a bunch of standing waves."

Right. Because the realistic motion of the bowed string is actually pretty bizarre.

Do you mean: any wave on a string with reflecting boundary conditions?Orodruin said:Any wave is a superposition of standing waves.

The entire point of a bowed string is that there is almost always a time-varying forcing that has a very complicated form. Once you remove the bowing and let the string ring, then all the interesting stuff damps out very quickly and you get something like a first-mode standing wave.In fact, the slow motion video you linked essentially shows this very well where the amplitude of the higher frequency modes are kept large as long as there is a source and decay rapidly once the source is removed, leaving only the ground state or as good of an approximation to it as is reasonable if accounting for a real non-idealized case. I would say it is definitely a question of semantics.

Oh, cool, that is very interesting! It makes perfect sense. That must be why you don't get good sounding minimalist guitars or violins without a body.AlephZero said:The vibration of the string doesn't produce the sound directly, The string diameter is tiny compared with the wavelength of the sound in air, so at best you would get a small amount of a dipole radiation from the opposite "sides" of the string. The sound comes from the vibrations of some resonant object (e.g. the wooden body of an acoustic guitar), and they are forced transverse vibrations, since they are usually not at the resonant frequency of the object.

You can demonstrate this by comparing the amount of sound produced by a tuning fork in air (which is inaudible unless the fork is very close to your ear), compared with when it is touching a solid object like a table top and making the table vibrate.

As others mentioned, standing and transverse are not mutually exclusive categories of waves. You could have a standing wave which is transverse or a standing wave which is longitudinal.Jackson Lee said:But if transverse wave could also be used to produce sound, then why we make so much attention on standing waves instead of transverse waves?

Orodruin said:Any wave is a superposition of standing waves. In fact, the slow motion video you linked essentially shows this very well where the amplitude of the higher frequency modes are kept large as long as there is a source and decay rapidly once the source is removed, leaving only the ground state or as good of an approximation to it as is reasonable if accounting for a real non-idealized case. I would say it is definitely a question of semantics.

DaleSpam said:Oh, cool, that is very interesting! It makes perfect sense. That must be why you don't get good sounding minimalist guitars or violins without a body.

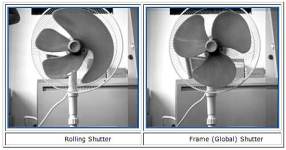

AlephZero said:That looks like artefacts caused by the rolling shutter in the camera. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rolling_shutter It only shows up when the strings are from top to bottom of the picture, not from side to side.

A nice example of how unreal it can make a digital image of a moving object:

I believe you may be thinking of the "longitudinal" wave in the sting. The transverse wave should be "across" relative to the direction of wave propagation.rcgldr said:Note that the bridge on a guitar or similar stringed instruments is oriented perpendicular to the strings. This would seem to imply that it's mostly picking up wave motion perpendicular to the string, but not just standing waves. The transverse (along the string) motion is relatively small compared to the perpendicular motion.

That is what I thought the op was asking (bad assumption on my part). I corrected my previous post. There are also longitudinal waves that travel at the speed of sound in the string or wire, but I assume these would produce frequencies way above the audible range.olivermsun said:I believe you may be thinking of the "longitudinal" wave in the sting. The transverse wave should be "across" relative to the direction of wave propagation.

Jackson Lee said:Thus, I felt surprisingly when watched that experiment. ?

Sorry, what I want to know is why those frequencise which are not harmonics will die out totally, because it seems we never take them into account, but not higher harmonics.olivermsun said:Well, first of all there are a couple things going on that cause standing modes in a plucked string that are not really "filtering."

If you excite the string by plucking (or most any other method), then the pattern you impose in the string will have nodes (the displacement is zero) at both ends. That's just because the ends of the string are (more-or-less) fixed in place by the "nut" and the "bridge." So you already know that the pattern has to be something like a sum of modes.

The exact modal content will depend only on where you pluck the string (assuming all you can do by plucking is to create a "kink" in the string).

The initial waves will travel away from the disturbance, traveling in both directions (half goes each way). The waves keep reflecting off the ends and so you will observe standing waves (caused by the superposition of waves traveling in opposing directions).

For a variety of reasons, the higher harmonics, which have a "sharper" shape, will die out faster; after a little while you mainly notice the fundamental mode of the string. This is probably the important "filtering" that goes on in the string.

In the bowed string, there is a complicated interaction between the bow and the string. You can imagine the string repeatedly sticking and slipping on the bow hair as the bow is drawn across the string. A key point is that the stick-slip cycles tend to be synchronized with the wave as it returns from the end of the string, so that the repeated forcing by the bow is resonant with the natural mode.

The string also has torsional (twisting) modes, which can have a different wave speed from the transverse modes. The complicated interactions between the torsion and transverse modes and the stick-slip of the bow are a major part of why bowed instruments are difficult to play with a "good" sound.

rcgldr said:That is what I thought the op was asking (bad assumption on my part). I corrected my previous post. There are also longitudinal waves that travel at the speed of sound in the string or wire, but I assume these would produce frequencies way above the audible range.

If the fundamental frequency of the string is 50 Hz then how would you excite a 49 Hz oscillation?Jackson Lee said:Sorry, you might misunderstand my meaning. What I want to know is why those frequencise except harmonics will die out totally soon. For example, harmonics are 50Hz, 100Hz, 150Hz... Then why some others, such as 49Hz or 88Hz will die out?

olivermsun said:If the fundamental frequency of the string is 50 Hz then how would you excite a 49 Hz oscillation?

Do you mean that those frequencies never exist at all?olivermsun said:Same question applies to 88 Hz.

My point in my (long) post was that the wave you excite in the string by plucking has to have nodes (zeros) at both ends of the string, so it has to be oscillate at some combination of harmonic frequencies.

olivermsun said:Same question applies to 88 Hz.

My point in my (long) post was that the wave you excite in the string by plucking has to have nodes (zeros) at both ends of the string, so it has to be oscillate at some combination of harmonic frequencies.

olivermsun said:At the moment before you pluck and release the string, there are no frequencies in the string at all. All you do is impose a shape on the string. If you analyze the shape using Fourier series, then all your terms have to look like ##\sin (n\pi x/L)## because the sum of the waves must have a node at each end. Those are exactly your standing modes, which oscillate at harmonic frequencies.