Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Matej Bresar's book, "Introduction to Noncommutative Algebra" and am currently focussed on Chapter 1: Finite Dimensional Division Algebras ... ...

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Theorem 1.4 ... ...

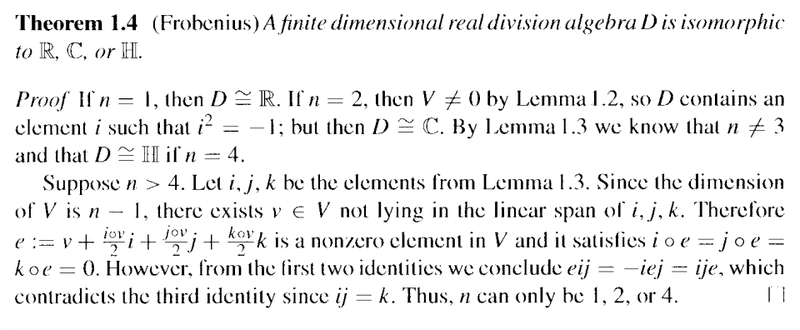

Theorem 1.4 reads as follows:

Questions 1(a) and 1(b)

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... Suppose ##n \gt 4##. Let ##i, j, k## be the elements from Lemma 1.3.

Since the dimension of ##V## is ##n - 1##, there exists ##v \in V## not lying in the linear span of ##i, j, k##.

Therefore ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k##

is a nonzero element in ##V## and it satisfies ##i \circ e = j \circ e = k \circ e = 0##... ... "My questions are as follows:

(1a) Can someone please explain exactly why ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k## is a nonzero element in ##V##?

(1b) ... ... and further, can someone please show how ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k## satisfies ##i \circ e = j \circ e = k \circ e = 0##?Question 2

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... However, from the first two identities we conclude ##eij = -iej = ije##, which contradicts the third identity since ##ij = k## ... ... "I must confess Bresar has lost me here ... I'm not even sure what identities he is referring to ... but anyway, can someone please explain why/how we can conclude that ##eij = -iej = ije## and, further, how this contradicts ##ij = k##?

Hope someone can help ...

Help will be appreciated ... ...

PeterThe above post refers to Lemma 1.3.

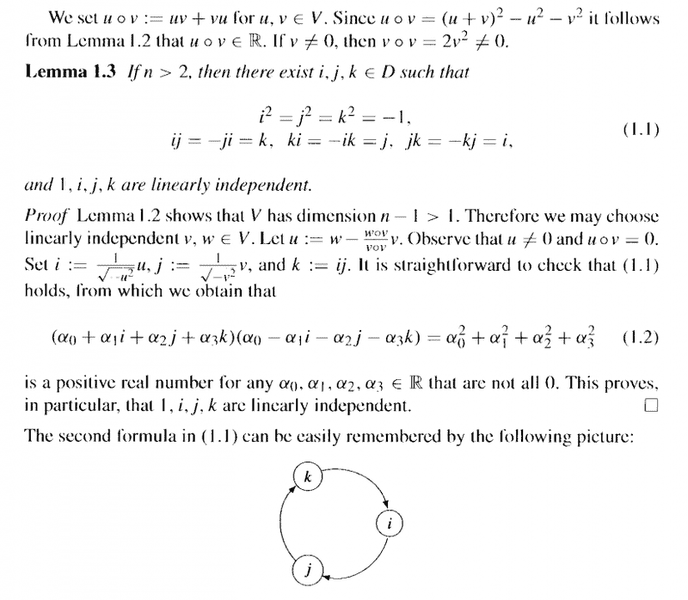

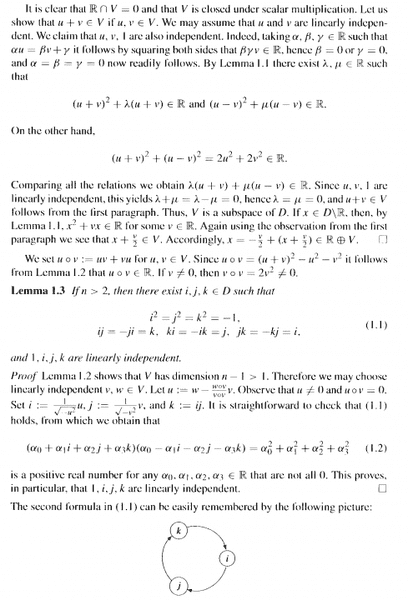

Lemma 1.3 reads as follows:

=====================================================

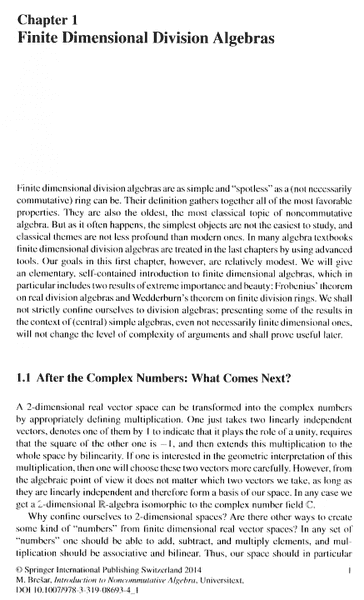

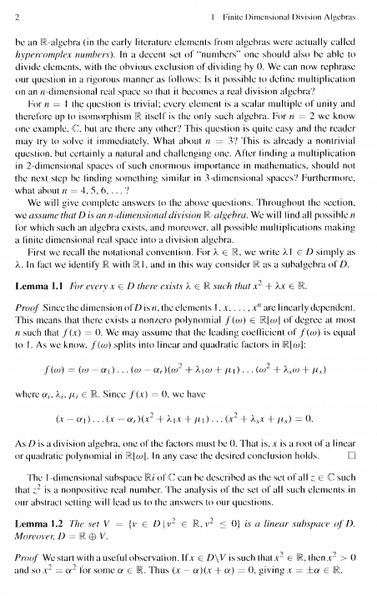

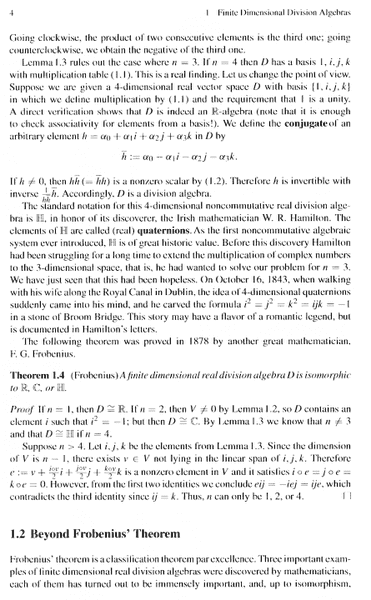

In order for readers of the above post to appreciate the context of the post I am providing pages 1-4 of Bresar ... as follows ...

I need help with some aspects of the proof of Theorem 1.4 ... ...

Theorem 1.4 reads as follows:

Questions 1(a) and 1(b)

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... Suppose ##n \gt 4##. Let ##i, j, k## be the elements from Lemma 1.3.

Since the dimension of ##V## is ##n - 1##, there exists ##v \in V## not lying in the linear span of ##i, j, k##.

Therefore ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k##

is a nonzero element in ##V## and it satisfies ##i \circ e = j \circ e = k \circ e = 0##... ... "My questions are as follows:

(1a) Can someone please explain exactly why ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k## is a nonzero element in ##V##?

(1b) ... ... and further, can someone please show how ##e := v + \frac{i \circ v}{2} i + \frac{j \circ v}{2} j + \frac{k \circ v}{2} k## satisfies ##i \circ e = j \circ e = k \circ e = 0##?Question 2

In the above text by Matej Bresar we read the following:

" ... ... However, from the first two identities we conclude ##eij = -iej = ije##, which contradicts the third identity since ##ij = k## ... ... "I must confess Bresar has lost me here ... I'm not even sure what identities he is referring to ... but anyway, can someone please explain why/how we can conclude that ##eij = -iej = ije## and, further, how this contradicts ##ij = k##?

Hope someone can help ...

Help will be appreciated ... ...

PeterThe above post refers to Lemma 1.3.

Lemma 1.3 reads as follows:

=====================================================

In order for readers of the above post to appreciate the context of the post I am providing pages 1-4 of Bresar ... as follows ...

Attachments

Last edited: