Yankel

- 390

- 0

Hello all,

I have a couple of questions.

First, about the mean value theorem for integrals. I don't get it. The theorem say that if f(x) is continuous in [a,b] then there exist a point c in [a,b] such that

\[\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx=f(c)\cdot (b-a)\]

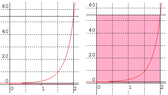

Now, I understand what it means (I think), but don't get the intuition (unlike the mean value theorem which is very intuitive). The integral is the area under f(x) between a and b. So how come it is equal to the height of f(x) at the point c, multiplied by the width ? How come there is a point c that represent the "average height" ?

The second question, I need to approximately evaluate

\[\int_{0}^{2}e^{x^{2}}dx\]

the answer is [2,2e^4], don't know why...

Thanks!

I have a couple of questions.

First, about the mean value theorem for integrals. I don't get it. The theorem say that if f(x) is continuous in [a,b] then there exist a point c in [a,b] such that

\[\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx=f(c)\cdot (b-a)\]

Now, I understand what it means (I think), but don't get the intuition (unlike the mean value theorem which is very intuitive). The integral is the area under f(x) between a and b. So how come it is equal to the height of f(x) at the point c, multiplied by the width ? How come there is a point c that represent the "average height" ?

The second question, I need to approximately evaluate

\[\int_{0}^{2}e^{x^{2}}dx\]

the answer is [2,2e^4], don't know why...

Thanks!